Editor's Week 2021

December 18 - 2021

Happy holidays to our readers. We'll be back in the New Year. KM

December 11 - 2021

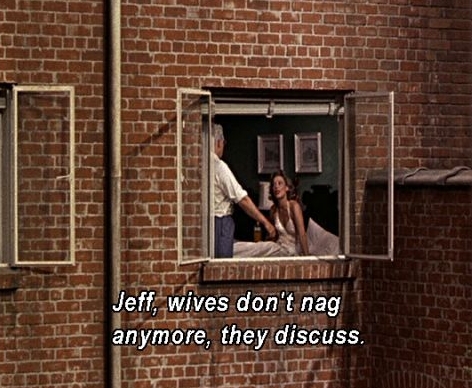

As we all know, Hitchcock had a keen eye for cinematic devices - such as the framing of shots. He liked to use built-in frames whenever he could, to help compose a striking or emphatic image. Marnie (1964) is full of them, amounting to a whole motif emphasising Marnie's combative nature, especially when Mark blackmails her into having to marry him. Marnie is obsessed with doors - the massive doors of safes, which she repeatedly burgles until Mark catches up with her. The motif here concerns Marnie's feeling that she and her mother have been victimised by men. She is determined - irrationally - to take her revenge. Even on her honeymoon, she wilfully excludes Mark from sharing her bed - so Mark, seemingly complying, says that he will sleep on the couch, 'light-years away'. For the moment, there is a door between them (see frame-capture below), and Marnie seems to prefer matters that way. Repeatedly we have seen her shut doors in Mark's face. However, he finally rebels at this treatment, and announces: 'Marnie, tonight the door stays open.' In a little child's voice, she protests, 'No!' But Mark enters the bedroom and pointedly closes the door behind him. Near the end of the film, after the death of Marnie's beloved horse, Forio, she goes again to rob the safe at the Rutland office, the business firm which Mark has inherited. (Both Forio and money are her compensations for what she feels has been done to her and her mother. Most of the proceeds of her burglaries are passed onto her mother, whom Marnie has set up in a small but luxurious house in a Philadelphia back street - almost a slum area. Another facade, notice. At the end of the street, which verges upon a waterfront, ships tower over the houses. The symbolism here seems to imply the yearning to escape that compels Marnie's irrational behavour. Equally, though, another of the film's motifs - a universalising one - seems to be that finally it's 'all one'. Mark has a pointed quotation which he cites to his sister-in-law, Lil, who fancies him. 'Careful, Lil. "When duty whispers ...".' The full quotation is from Milton '('Paradise Lost', I think) and its gist is in the two lines that Mark leaves out: 'So nigh is grandeur to our dust,/ So nigh is God to man.' (In God's, i.e., the Creator's, eyes, all may indeed be one - another nice poetic touch of the film: script by playwright Jay Presson Allen, btw.) I don't think I'm overinterpreting the sort of feelings that Marnie brings with it for an alert viewer. I always find it extremely moving. But we were talking about natural 'frames' in Hitchcock, and notably doorways. Hitchcock could be daring, often. In Rebecca (1940), there's at least one shot where the newly-married 'I' character (played by Joan Fontaine), now installed in husband Maxim's family mansion, Manderley, finds herself dwarfed by the immense doors there. Hitchcock even includes at least one shot where the door handles seem to be at almost shoulder height! (Could he have been remembering Lewis Carrol's 'Alice in Wonderland' - or possibly 'Alice Through the Looking-Glass' - in which Alice drinks a magic potion which shrinks her to child-size?) And speaking of Rebecca ... It's a film in which windows form another motif. At one point, the evil housekeeper Mrs Danvers almost persuades 'I' to jump to her death from the window of Rebecca's bedroom. At another point, the smarmy Favell character (George Sanders) hops into a ground-floor room through a conveniently open window - he is nothing if not insouciant - lending the characterisation a suitable dramatic emphasis. Of course, Hitchcock's definitive 'windows' film is Rear Window (1954), where each wimdow frames a separate story which unfolds during the film. I'm also reminded of Stage Fright (1950), in which Hitchcock repearedly frames shots as if from the wings of a theatre - even where the action is taking place in a non-theatrical setting. Finally, I think of characters who are shown putting their head out a window to address another. Memorably, there's the mother in Shadow of a Doubt (1943) who calls out cheerfully to Uncle Charlie, a serial killer; and in Frenzy (1972) there's the red-haired mother of serial-killer Bob Rusk whom we see put her head out an upstairs window to call to her son in the London street below - something like 'Will you be home for tea?'! (Both mothers are totally unsuspecting, clearly.) In sum, Hitchcock used visual motifs cinematically and often ingeniously.

December 4 - 2021

A friend has suggested that I blog on Hitchcock and heights - so here goes. A list of titles fitting this category includes Blackmail (1929), Jamaica Inn (1939), Saboteur (1942), Vertigo (1958), North by Northwest (1959), and Psycho (1960) - think of poor Arbogast pushed down the stairs by a knife-wielding Mother. Have I left any out? The frame-capture below shows the detectives in Blackmail who, having chased poor Tracy (the blackmailer) onto the roof of the British Museum, recoil from the sight of his death - he has just fallen through the Museum's distinctive dome. (The builders should have used unbreakable glass but, ah well, what is done is done! And Hitchcock needed it to happen that way!) Such a climax suited Hitchcock who once told a class of cinema students that he always tried to work in 'the realm of the visual'. (He had been asked why so many of his films feature staircases.) Now, I have called the blackmailer 'poor Tracy' because like so many of Hitch's films, this one makes us not unsympathetic to the nominal villain. Tracy, unemployed, had happened to be loitering in the street waiting to visit the artist Crewe - no doubt to put the squeeze on him for some money - when he saw Alice (Anny Ondra) exit the studio, and then upstairs found that Crewe was dead. Meanwhile, Alice in her haste had left one of her distinctive gloves behind at the scene of her crime - when Crewe had tried to rape her she had knifed him in self-defence. Aghast, she had run away. Later, her boyfriend, the rather smug detective Frank (John Longden), who happens to be assigned to the Crewe case, had found the other glove and had kept it without telling his superiors. In sum, there are several crimes committed in Blackmail and together they represent a multi-pronged travesty (or miscarriage) of justice. As so often in Hitchcock, we may be left with an uneasy feeling that, after all, this is how the world goes - which doesn't greatly lessen our unease. (I think it was Robin Wood, or someone, who wrote of the 'bitter taste' that a Hitchcock film may leave us with.) Of course, there is the bigger satisfaction of the excitement and suspense that the film has given us. And, moreover, it is 'only a film' as Hitchcock would say. Ultimately, he concerned himself with 'the realm of the visual'. Nor was he original in his idea for Blackmail's climax. It had actually been suggested to him by a young Michael Powell, who was familiar with the Britsh Museum and its glass-domed Reading Room. In turn, it's likely that Powell himself got the idea after seeing John Longden in Palais de Dance (Maurice Elvey, 1928) which had used to same locale for a similar climax of its own! And of course falls from great heights had numerous precedents in the stage melodramas of the 19th century. For Hitchcock, the effect on the audience was just about everything. True, he didn't think to underpin the effect here by a line of under-stated dialogue such as Roger Thornhill's in North by Northwest: 'This won't do, we're on top of the Monument!' But then, Tracy is a loner, whereas Thornhill is accompanied by Eve Kendall whom he says he will make Mrs Thornhill 'if we get out of this alive ... That's a proposal, sweetie!' Exploiting a film's (or a situation's) love-interest was something that Hitch was still learning to do. He still hadn't fully mastered it, perhaps, by the time of Saboteur: as he later said, the situation would have been even stronger if he had had hero and heroine both clinging from the Statue of Liberty together. On the other hand, having the villain fall to his death was something that the Effects Department could help him with very well. In a kind of 'vertigo effect', we see Saboteur's villain plummet to the ground. One refinement that Hitchcock added in North by Northwest was to have the villain, Leonard, let out the most blood-curdling of screams as he falls to his death, and to hear the scream receding in intensity as he plunges away from us. But that's enough for now ...

November 27 - 2021

Sorry. Another Hitchcock-related matter arose and had to be dealt with. [KM]

November 20 - 2021

I ended, last time, by evoking the 'baffled opponents' in Hitchcock, and suggested: 'Think of Mrs Danvers in Rebecca (1940) or of the Martin Landau character in North by Northwest.' Of course, not all of Hitchcock's villains have to meet the extreme fates of those two, i.e., the immolation of Mrs Danvers in a burning mansion, the plummet from a cliff of Leonard (with accompanying receding cry). But Hitchcock did usually provide us with a character to detest, as he liked to tap into a wide range of our emotive responses. If Stage Fright (1950) is one of his weaker films, that may have something to do with how we aren't given a clear-cut villain until the very end. Is it - surely not?! - the ambiguous Marlene Dietrich? Or else, one of those other skulking backstage types? Well, no, it turns out to be the weak Richard Todd character, who has expressed interest in the Jane Wyman heroine but who finally admits to her - threateningly - that he is the man the police are after. Rather more satisfying, I find, is another of Hitchcock's 'theatrical' films, namely, The Paradine Case (1947) - one of its conceits is that the English law courts, specifically the Old Bailey, are a place of drama, not least because of the pomp and regalia of judges, barristers, etc. Charles Laughton is almost perfect for such a role, and plays Judge Horfield who presides over the trial of Maddalena Paradine for allegedly poisoning her husband, supposedly because she had fancied Paradine's loyal manservant, André Latour. (All of which proves true!) Less grand, unfortunately, is the young Gregory Peck who play's Mrs Paradine's defence barrister, Anthony Keane. It's no surprise to learn that Hitchcock would have preferred an older actor, such as Laurence Olivier (fresh from playing Henry V and soon to embark on Hamlet, followed by Richard III) or Ronald Colman. Hitchcock well knew that 'courtroom drama' was a particularly suitable term for what he had in mind. He also knew that there were very many famous trials in English judicial history, the majority of which had been held at the 'new' Old Bailey since it was completed in 1902. Further, Hitchcock would have recognised in Robert Hichens's 1933 novel elements drawn from just such actual trials. My research suggests that there were two sensational English murder cases that had particularly influenced Hichens. The first was that of Madame Fahmy, an attractive Englishwoman who in 1923 was acquitted by a jury after she shot and killed her husband, an Egyptian prince, at London's Savoy Hotel. At the trial, it was suggested that the prince had been intimate with his male secretary (cf. the probably gay Latour in Hichens's novel). The fact that Madame Fahmy herself seems to have been a woman of 'loose morals' (a close parallel with Mrs Paradine) wasn't revealed to the jury - her famous advocate Edward Marshall Hall (cf. the film's Keane) saw to that. The other murder case was that of Florence Maybrick, a young American woman found guilty of poisoning her English husband at Liverpool in 1889. Note that Mrs Paradine's alleged murder weapon (or vehicle) was the 'fatal glass of burgundy' she had given her husband. But Mrs Maybrick's husband seems to have had a violent disposition, probably the result of his chronic hypochondria (again with parallels in The Paradine Case). It's also likely that he discovered that his wife was having an affair with a man named Brierley. Very importantly, Robert Hichens based his novel's pivotal Keane/Horfield antagonism on a real-life clash of temperaments between Edward Marshall Hall and the most feared criminal judge of his time, Mr Justice Avory. Marshall Hall was handsome, and said to be 'at his best when able to identify himself strongly with his client's cause'. Keane in The Paradine Case has lines to precisely that effect. In contrast, Mr Justice Avory had been a merciless criminal prosecutor who 'became an icy judge, one who disregarded all except purely legal considerations'. He was known as a hanging judge, something that the novel's sadistic, as well as lecherous, Lord Horfield certainly is. So too is Horfield in the film, though the character is necessarily watered down. Incidentally, I would dearly love to have seen Hitchcock's original cut of his film, which ran close to three hours, as opposed to its present running-time of less than two hours (whittled down by producer David Selznick and then further for TV). A lost Hitchcock masterpiece? Next time: more on Hitchcock's 'detestable' characters?

October 30 - 2021

A friend this week messaged me to say that she was watching and enjoying a film - although one I had not heard of. (Let's leave it nameless.) A short time later she messaged me again. This time her tone was different. She wrote: 'It was good up until the very bloody showdown. I don't know why everything American always has to end in bloodshed.' Hmm, I ventured, it probably has a connection to the 19C stage tradition - appropriated by American silent director D.W. Griffith - of a spectacular climax. Simplified, the idea has become a jokey maxim, 'Cut to the chase!' Think of Griffith's Way Down East (1920) in which Lillian Gish clings for her life to a large chunk of ice careering down a river towards a steep waterfall; Richard Barthelmess runs along the river bank, seemingly helpless to save her. (Any ideas?!) As part of Griffith's technique, which he had used from at least Birth of a Nation (1915) onwards, he keeps cutting to the danger ahead. Later, one of Griffith's biggest admirers, Russian director Sergei Eisenstein, identified the technique in his famous essay, "Dickens, Griffith, and the Film Today". Now, although my flimsily-bound, one-volume copy of Eisenstein's 'Film Form' and 'Film Sense', containing that essay, has come apart, and I haven't read it lately, I believe I recall the Dickens connection mentioned in the essay's title. For Charles Dickens (1812-70), too, had used - and indeed helped pioneer - that technique in novels like 'A Tale of Two Cities' (1859). There, the question posed at the climax is: can ne'er-do-well Sydney Carton rescue Charles Darnay, fiance of Lucie Manette, from the guillotine? (Answer: yes, he can, if he is brave enough!) Notice - even from that brief description - the complex way in which Dickens is playing with the reader's emotions. Also, note the added excitement at the end of the novel, when the rescued Darnay, acompanied again by Lucie, has successfully eluded death on the gallows, but must further escape the baffled French authorities when the latter find out that they have been tricked. ('Cut to the chase', indeed!) I'm sure that Alfred Hitchcock learnt much from Dickens - after all, he had read four Dickens novels at school and later owned a complete set of the English author's works. (My thanks to Bill Krohn who once told me about that set which he had noted when he was allowed to take inventory of Hitchcock's bookshelves after his death.) In any case, the proof is in the films. Dickens's technique is much evident in The Man Who Knew Too Much (1956) in which Hitchcock sees fit to follow a big climax at the Royal Albert Hall with another, in which the kidnapped boy, Hank McKenna, must be rescued from a foreign embassy in London. At this second climax, as Hank's parents combine to find their son, Hitchcock uses much cross-cutting ... Hmm. I shan't further illustrate my point by an obvious example taken from the Mount Rushmore climax of North by Northwest (1959) - hero and heroine in peril on a mountain while pursued by vengeful baddies - but will refer instead to the climax of the underrated Torn Curtain (1966). Despite vindictive opposition from an ageing ballerina, played by Lila Kedrova, Paul Newman and Julie Andrews flee East Germany and pull off a succession of last-minute escapes. Kedrova even follows them on-board their escape ship to Sweden. At the very last minute, she detects their supposed hiding-place - a costume basket being winched ashore from the ship's deck - and orders the ship's crew to fire on it (see frame-capture below). Meanwhile, hero and heroine have managed to swim ashore and set foot on safe neutral territory. The baffled opponent is as much a part of the tradition I'm evoking as the physical flight of hero and (usually) heroine to safety. Think of Mrs Danvers in Rebecca (1940) or of the Martin Landau character in North by Northwest.

October 23 - 2021

For many years, well into the 1950s, Hitchcock said that his favourite of his films was Shadow of a Doubt (1943) which, because of wartime conditions, he had chosen to film largely on location rather than in the studio. He also admitted that he had enjoyed the opportunity to work with top playwright Thornton Wilder ('Our Town') and to have him guide Hitchcock on the minutiae of small-town American life. (Hitch and family had only settled in the USA three years earlier, remember.) What many visitors to Santa Rosa see first is its railway station with its wide platform - that's how I first saw Santa Rosa myself when I visited there many years ago. In Hitchcock's film, it's also how Uncle Charlie (Joseph Cotten) gets his first impression of the town, having decided to flee there to evade the searching police who - rightly - think that he could be the Merry Widow serial-killer. He rides the train to Santa Rosa, from which he will depart the same way near the end. By then, his astute niece, young Charlie (Teresa Wright), has stumbled on who he is - the basis of a dramatic scene in the Santa Rosa Library after closing time, when she has begged the librarian to allow her to look up a newspaper as matter of urgency ... The convincing, well-observed characters make up a large part of Shadow of a Doubt's effectiveness, the lady librarian among them. (She isn't used to matters of urgency in laid-back Santa Rosa, nor to her authority being pushed to allow concessions to her usual routine.) Young Charlie's father, Mr Newton (Henry Travers), works in a bank in the town's centre, which makes him another representative of the town. But he, too, isn't used to any disruptions from routine, and is embarrassed when Uncle Charlie deliberately makes a scene in the bank, apparently just to satisfy his own sense of importance! Gentle (not to say meek) Mr Newton is no notorious serial killer, and so Uncle Charlie considers himself entitled to take such liberties for his own fun! Something inside him prompts him to want to draw attention to himself, even at the risk of the personal danger it brings. (Compare the spectacular attempt he makes on young Charlie's life by locking her in the garage with the car's motor running - Uncle Charlie having secreted the engine key. That 'accident' would undoubtedly have made headlines and put a spotlight on the other members of the Newton family, including its visitor, Uncle Charlie.) Santa Rosa's bank has always been a landmark of the town. So has its night life, I gather, and this allows Hitchcock's film to include a scene in the Til' Two Bar where Uncle Charlie takes his niece for a serious late-night discussion of what exactly she intends. He has already taken advantage of young Charlie's reluctance - an opposite trait of his own - to make a scene. He, on the other hand, has positively revelled in the attention he has been getting in the Santa Rosa community, seeming to put it about that he is a major figure back East, possibly even a war hero. (However, the only actual reference to the War in the film is a discreet placard in Mr Newton's bank that reads, 'Buy war bonds now'.) Another likely contribution of Thornton Wilder to the film is its opportunities for scenes of gentle humour. A favourite of mine is Ann Newton's opinion of herself as already grown up. In the frame-capture below, note her disdain for the gift she (Edna May Wonacott) has been given by Uncle Charlie, a child's teddy bear (is it?), whereas her brother Roger seems thrilled by his gift. Hitchcock found both children in Santa Rosa, shortly before filming began. To be continued.

October 16 - 2021

For technical reasons, I wasn't able to make my own frame-capture this time, nor show Edmund Gwenn, a memorable character-actor in Foreign Correspondent, in the particular image I wanted. So, instead, here's a photo from off the Web of the tower of Westminster Cathedral - the tower from which Gwenn's character, Rowley, falls in a dramatic moment. (Btw, characters falling off buildings had been shown in other directors' movies previously - at least, I can think of King Kong falling from the top of the Empire State Building in the 1933 movie bearing his name. Hitchcock had already shown the panicked villain in Blackmail, 1929, plummeting to his death from the dome of the British Museum and landing inside that building's Reading Room.) All in the name of giving his films 'visual interest', no doubt! This week, I would like to pay tribute to Gwenn (1877-1959) who appeared in no fewer than four Hitchcock films: The Skin Game, Waltzes From Vienna, Foreign Correspondent, and The Trouble With Harry. Always, he was able to make his character sympathetic to audiences, even when someone like Hornblower in The Skin Game (1931) may seem not to deserve it, or at least have an unfeeling side. (In that film, Gwenn's character is decidedly ambitious, an enterprising up-and-comer who infringes on the property rights of the patrician Hillcrist. Which makes for good drama, undoubtedly. Hitchcock loved such not-easily-resolvable, or ambiguous, situations in his films.) Always, Gwenn's chirpiness helps win us over even when, in The Trouble With Harry (1955), he comes close to whining ('Oh Sammy, must we?'). He was ideally cast in George Seaton's Miracle on 34th Street (1947) where he played Kris Kringle, the Santa Claus figure employed by a department store! Now, in a film artfully filled with climaxes - without the story ever seeming overloaded - the Westminster Cathedral scene is itself extended while, all the while, suspense mounts. The cathedral is a Catholic one, not to be confused with the anglican Westminster Abbey nearby long made famous by royal occasions such as coronations. Hitchcock carefully identifies his locale, noting the requiem mass ('You know, a mass for the dead', says Rowley helpfully) which is taking place in the main chapel. Rowley uses the mass as an excuse not to go inside the chapel but to immediately escort Johnny up to the cathedral's observation deck in its tower - a tourist attraction, it seems. One of the chilling things about the seemingly amiable Rowley is his intentness to kill. That intentness is seen on his face when - the other tourists finally having gone down in the lift - he rushes at Johnny from behind, his palms outstretched for maximum pushing-power. Now Hitchcock cuts to an extreme long-shot of a body falling from the tower, then immediately to a shot of Johnny - alive - explaining to fellow-journalist Stebbins what had happened, how something had made him step aside in the tower, thus causing Rowley to go over instead. In sum, Foreign Correspondent is a film of multiple climaxes and multiple villains (Krugg, Rowley, the unflappable Fisher), and almost non-stop menace. A tour de force! Finally this time, my thanks to occasional correspondent John C. (who in the past has discussed with me Dial M for Murder and Vertigo) who this week sent me some thoughts on Foreign Correspondent. He noted the possible influence of Hitchcock's film on another 'umbrellas' scene, in Frank Capra's Meet John Doe (1941). John cites the film's script: 'As far as the camera eye can see the reflection on the wet umbrellas creates a strange and mystic light'. Astutely, he notes: 'Gary Cooper even wears a light grey overcoat like Joel McCrea', thus making their movements in the respective scenes stand out. Also, John reminded me of a movie precedent for umbrellas in rainly Amsterdam, namely in the short film by Joris Ivens aptly called Rain (1929). I saw it many years ago. At the very least, if Hitchcock saw it, it would have reinforced his association of Amsterdam with umbrellas. Also, John reminded me of the similarity of Foreign Correspondent's assassination scene (one close-up in particular) and the famous shooting on the Odessa Steps seen in Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin (1925). Thanks, John!

October 9 - 2021

'The fact is, I practise absurdity quite religiously', said Hitchcock. He was speaking in the late '50s, at about the time of North by Northwest and when the Theatre of the Absurd was peaking (Samuel Beckett's 'Waiting for Godot', etc. - maybe Hitchcock was thinking of his own crossroads scene, in his new film). Well, Hitch was right, and 'absurdity' was indeed something he had practised for a long time in his movies. Take Foreign Correspondent, about which we blogged last time. What could be more absurd, on analysis, than that film's assassination scene on the steps of Amsterdam Town Hall? Recall that it involves the shooting of Van Meer's double - posing as Van Meer himself - just as arriving dignitaries are being watched by a large crowd, many of them with umbrellas raised because rain has begun to fall. But seemingly, the rain is the least of the hazards that the elderly Van Meer must face. As he mounts the wide steps, a news photographer steps forward and asks to take his photo with a plate camera and flashgun. The photographer raises the camera - large enough to conceal a loaded pistol - and shoots Van Meer in the face at close range. Hitchcock seems to have got exactly right what the bloodied face of an assassination victim looks like. I remember once consulting a book of forensic photographs (in the Monash University Law Library) and seeing an identical image of a shot man ... So, what is 'absurd' about the scene? Answer: the fact that both participants - photographer and victim - must have been paid for their services, presumably by the head of the Universal Peace Party, Stephen Fisher, who has been looking on. Think about it. First, what could the 'victim' possibly have been told? 'We're going to pretend to shoot you in the face but don't worry, we'll use blank bullets'? (Hmm. If so, the individual must have been prepared to go to gaol for a long time.) Well, they must have paid him a whopping amount, if that were the case! And what could they possibly have told the photographer? 'Don't worry, your gun will be loaded with blanks? The onlookers will be so shocked, you'll be able to make an escape into the crowd and we'll have a car waiting for you'? If so, again the 'fee' must have been massive! No, in fact the scene is absurd - and just the sort of thing that Hitch would have relished! He was probably thinking of the triumph of pulling off such a scene, and thereby almost identifying with its two central figures! Of course, the screenplay would have needed to include some sort of 'explanation'. And it's there. When the action later moves to the windmill scene, and Johnny stumbles upon the kidnapped (real) Van Meer, the old man tells him, 'They want the world to think that I've been assassinated to conceal the fact that I am in their hands.' Interestingly, Hitchcock later professed to despise directors who don't much worry about plausibility and who say, 'We'll cover it in a line of dialogue!' Clearly, he was generalising, and making exception for when his own high-style would allow him to get away with it! Now, a couple of final observations about the Town Hall scene. I have often claimed that there is a strong element of 'Sapper' - the English novelist of 'pugilistic' popular fiction, a contemporary of the much more genteel John Buchan - in Hitchcock. In one of Sapper's novels (I once read several of them) there's again the device of elaborately staging the killing of a victim to conceal that he is really still alive. But I'm sorry, I don't remember which one. Lastly, I'm practically certain that there's a slightly earlier film than Foreign Correspondent in which there's another 'sea of umbrellas' - in which case, Hitchcock almost certainly saw it and was impressed by the visual effectiveness of it.

October 2 - 2021

There are no train scenes (see last time) in Foreign Correspondent (1940), but it gets around anyway. Someone has called it a 'treasure chest' of Hitchcock, and I agree. It is surely his busiest film. Literally all the natural elements are included, by which I mean sea, sky, wind, rain, with their appropriate modes of travel - ship, plane, car, and finally a luxury air clipper which of course crashes into the sea, because Hitchcock has been lulling us to this point. (See what was said last time about 'cosiness'.) That watery scene acts as a metaphor for the reality of war which we learn has been declared just before the plane flying Johnny Jones (Joel McCrea) back to the lights of America takes off. Among the other passengers on board are Carol Fisher (Laraine Day) and her renegade father, Stephen Fisher (Herbert Marshall), who has used his position as head of the Universal Peace Party to secretly further the cause of war. (A typical Hitchcock reversal there.) Like a musical tone, the drone of the plane initially strikes Carol as a pleasant sound, and she expresses the wish that they might all fly on like this 'forever'. The audience sees how whimsical she is being - and very soon she sees it for herself. Once Carol's father learns that he will be arrested when the plane lands on American soil, he knows that he must reveal to her how he has 'used the tactics of the country I grew up with'. That revelation coincides with the metaphorical plummeting of the plane into the sea. Meanwhile, an elderly lady passenger simply denies the reality of what is happening to them all ('I shall report this nonsense to the British Consul when we land') - until at that very moment a stray bullet from the ship that has been shooting at them strikes the lady dead, and she sinks to the floor. Again Hitchcock is making a point here. I was reminded of the moment in The Lady Vanishes when the Cecil Parker character - a weakling who has been cheating on his wife - thinks to placate the enemy soldiers firing on the train by waving a white handkerchief towards them, only to be immediately shot dead, murmuring 'You don't understand.' In Hitchcock's estimation - it's fair to say - some facts are simply true and cannot be twisted into what they are not. A bullet is unambiguous. Yes, Foreign Correspondent is 'a propaganda film' but it deals in facts nonetheless. Once Fisher comes to his senses, he is able to tell Carol that he had made a wrong choice - and his inner strength of character surfaces when, finally, he is able to sacrifice himself to save his daughter and the man she loves, i.e., Johnny, as well the clipper's other passengers. Now, I said above that Foreign Correspondent is Hitchcock's busiest film. I meant that it is crammed with lively inventiveness, no doubt a sign of Hitchcock's reunion with the screenwriter he called his 'best constructionist' - Charles Bennett, who had been resident in Hollywood for several years. Certainly, few writers were more adept at creating strong scenes, and giving them a plausible connection, than Bennett. Take the film's celebrated scene set in a windmill in Holland which the foreign agents have made their hideaway and where they hide the kidnapped diplomat Van Meer (Albert Basserman) whose age and frailty, but also courage, are readily apparent to us. (It's a fine performance by Basserman.) The action takes place on literally several levels, and the lighting is aptly chiarascuro (aptly, not least because Holland was the country of famous painters like Rembrandt). See frame-capture below. Note that when Johnny first decides to investigate this particular mill because it seems the only possible hiding-pace for the foreign agents whose car had mysteriously vanished from an open road, he isn't at first aware that Van Meer is concealed there. Further, in a suspenseful moment, his coat becomes entangled in the mill's gears, and it seems that Johnny's arm could be torn off. Retreating further up the stairs, after he sees other agents approaching the mill - as to a rendezvous - he stumbles on Van Meer, drugged and bound. Then, realising that he will need help, he makes his provisional ecape by clambering down the outside of the mill. Note that Hitchcock and Bennett further 'explain' the mill as a signalling 'device' used by the foreign agents to a plane that circles overhead. Somehow, none of this detail seems to overload the screenplay, such is Bennett's and Hitchcock's adroitness. Rather, it all adds to our breathless appreciation! Even the car's disappearance had been cleverly managed, a piece of sleight-of-hand that seems impossible: now you see it, now you don't! It's all in the editing, of course. Typical Hitchcock! (To be continued.)

September 11 - 2021

Several times we have referred here to Hitchcock's Vague Symbolism - because its resonance is multi-valent and non-specific. Take the episode that ended the First Season of 'Alfred Hitchcock Presents', called "Momentum". Below is a frame-capture of Hitchcock's intro (echoed later by his outro) to "Momentum". Note the watching eye. Hitch refers to it as all-seeing - as watching us watching him. He notes that it 'never sleeps'. In the story that immediately follows we promptly begin to sense the relevance of this. The story in a nutshell is about a man, Dick Paine (Skip Homeier), who shoots his ex-employer (needlessly as it turns out) - a man named Burroughs - in order to recover money owed. Dick refers to life as a 'rat-race', and, being unemployed, he faces the imminent possibility that he and his wife Beth (Joanne Woodward) may soon be evicted from their apartment for arrears in rent. On his way to confront Burroughs, Dick stops off at a bar. To the barman he observes, in time-honoured fashion (cf. the original title of the 19C novel, 'Little Dorrit'), that the rat-race is 'nobody's fault'. He asks the barman, a friend of his from way back, to help him out, but the barman has just lost a heap of money at the races. Arriving at Burroughs' house, Dick sees him paying money to an unseen person (the view is obscured) from out of a locked cashbox. When the unseen person leaves and Burroughs' lights go out, Dick breaks in. But Burroughs has heard him. There's a brief scuffle, and Burroughs is shot. From here on, the episode is one of rising tension and multiple climaxes. These are so representative of how a typical episode of AHP works, that I'd like to ennumerate them. Next day, when Dick is back home, there's a sharp rap on Dick and Beth's door - it proves to be the janitor wanting to show a prospective tenant the apartment. Of course, the audience wonders if the police are at the door. Dick realises that he and Beth must sneak away. But over the street he spots a man loitering, who appears to be watching their apartment. He tells Beth to go anyway, and he'll try and join her at 11 o'clock at the main bus depot. Boldly, Beth leaves, crossing the street directly in front of the loitering man who, after a moment's hesitation, follows her. But before Dick can sneak out the back way, as he had planned, there's another rap at the door - and it's the loitering man returned. He forces his way in, then proves to be only a process-server who has a debt-notice to serve. However, Dick, brandishing a gun, decides that he must lock the debt-collector in a closet, which he does - but gets wounded by a shot from his own gun. He staggers out, and whistles up a taxi - just evading the police who finally arrive to question him. Gentle reader, several more climaxes, or false climaxes, still remain! Briefly now ... As Beth waits on a seat at the bus station, a man behind her makes a pass at her - but Beth merely turns her back on him. Meanwhile, in the taxi, Dick tells the driver to stop. This prompts the driver of a passing car to slow down and ask, 'Need any help?' Dick calls out (his gun on the taxi-driver), 'No thanks!' Then he slugs the taxi-driver and leaves him in some roadside bushes. Finally, driving the taxi to the bus depot, Dick jumps out (causing a traffic snarl) and hurries inside, thinking that Beth may have had to leave for San Diego without him. But that bus is running late - and Beth spots Dick before he spots her. At that moment, Beth drops her purse, and there is plenty of money inside. We now learn that she had got to Burroughs before Dick did, and that Burroughs had handed her the overdue money without demure. (Beth had been the unseen person when Dick had peered through Burroughs's window.) Dick, finally succumbing to the shotgun wound that he had received, slumps back, saying, 'It's a rat-race. You run all day ...' (Btw, "Momentum" was directed for AHP by Robert Stevens, from a story by Cornell Woolrich.)

September 4 - 2021

I thought some of you might be interested in know that there's a new edition out of Frank Baker's excellent novel, 'The Birds' (1936, from memory). Once again, it's re-published by Valancourt Books, and includes the Introduction by yours truly. Illustration of new cover below. My thanks to Patrick Wikstrom for spotting the new edition and letting me know. I can't immediately locate my own copy of the book, so I can't quote myself (!) directly. The important thing to know is that Frank Baker was working at Daphne Du Maurier's publisher in London when he brought out his novel, and it's highly likely that she read about it at the time - although she later denied it. (Du Maurier, of course, wrote her short story "The Birds", the official source of Hitchcock's film of that title. Her story was included in a collection of her stories, published about 1952.) Also importantly, the novel bears some close correspondences to Hitchcock's film. For example, both novel and film have a scene in which birds attack a person who takes refuge in a telephone box. So it's plausible to think that Hitchcock himself, who was still working in England back then, may also have read or heard something about the Baker novel. When Hitchcock's The Birds came out in 1963, Baker actually threatened to sue Hitchcock and Universal for plagiarism. Personally, I think he had quite a good case.

August 14 - 2021

No "Editor's Week" this time. But do please read the News item from this week.

July 31 - 2021

Continuing on from last time, the boathouse scene in Rebecca may be my favourite scene of all in that fine film. Patricia White's monograph says insightful things about it. Allow me to quote some of her commenary on it. 'The pervasive presence of Rebecca, the most distinctive achievement of the novel,' she writes, 'poses a problem for a visual medium. Hitchcock's solution, which demanded multiple rewrites on [Joan] Harrison's part even as shooting was under way, was to use a present-tense camera to "narrate" Rebecca's death as Maxim details the events that transpired the night she taunted him. Choosing not to show Rebecca in flashback preserves ambiguity about Maxim's culpapility and allows her to maintain her larger-than-life status while aligning her with the power of cinema. ... When Selznick saw the rushes, he responded with uncharacteristic brevity; he found it "wonderful".' (White, p. 37) White has many interesting comments and factual matters to share. Having commented on the 'dreamlike' tension created by the boathouse scene, she later gives another example: 'Rebecca's eerie theme, distinguished by the use of an electronic instrument called a novechord, [further] conjures her pervasive presence.' (p. 48) (That same theme is repeatedly associated with the sea - where Rebecca's body ends up.) If Hitchcock didn't specifically ask composer Franz Waxman for such a cue, he (or Miklos Rozsa) certainly remembered it when he made Spellbound (1945), in which another electronic instrument, the theramin, figures prominently, evoking the amnesia or 'spell' in which Ballyntine (Gregory Peck) finds himself caught. (That's another repeated element: I've already noted the spell or 'forcefield' under which Rebecca's Manderley is seemingly cast for much of its length.) And something else I've previously commented on is a near-sterility, a seeming 'impotence', of everyone at Manderley. White mentions this: 'The [abrupt] dispersal of the company [after the ball], [and] the utter absence of smart, modern women "I's" own age ... highlights her childishness and keeps the narrative focussed on the isolated couple as they experience intrusions from the past.' (p. 88) (About 'I' herself, White comments amusingly that when she first comes to Manderley she could be mistaken for 'a member of the public, admitted to tour the home on Tuesdays' - p.70.) But finally, I want to say something about the character Jack Favell (George Sanders - later one of the stars of the Bette Davis film All About Eve, 1950). He counterpoints the subdued character of Maxim, and is Rebecca's main comic relief. Clearly a bit of a bounder, he consorts with Mrs Danvers, which is explained by their both having been close to Rebecca, and by something the novel tells us, that he had been seduced by her. I love the early moment in the film (see frame-capture below) in which Favell catches 'I' unawares and asks her almost cheekily, 'Looking for me?' He is standing at a window behind her and his voice makes her whirl around, startled. We had not been shown the window earlier in the scene, so we are startled, too. (Hitchcock often had windows placed conveniently for an effect he might want. Come to think of it, White mentions a window in 'I's' bedroom opened by Mrs Danvers, 'strangely adjacent to the bed ... [looking out] onto the foggy night' - p. 87.) Next minute, with more cheeky insouciance, he has thrown a leg over the sill and bounded into the room! In the frame-capture, notice the cross-shaped shadow across his face. It is scarcely a Christ-symbol - contrast Blackmail, 1929 - but more of an attempt to characterise him as villainous. Actually, it was also in Blackmail, I think, that Hitchcock deliberately threw a shadow on a villain's face to make him resemble the villain from stage-melodrama, preening his moustache! And Favell does return later in the film to blackmail Maxim. Jumping into Maxim's car outside the courtroom during a lunch recess, he - insouciantly - helps himself to a piece of chicken and then tosses its bones out the car window. 'What does one do with old bones? Bury them, eh what?' Earlier, he has also been given the key line reflecting directly on Maxim: 'That temper will do you in yet, Maxim.' (Maxim had punched him.) That gives us justifiable pause for reflection ...

July 24 - 2021

I recall that Penelope Houston, Editor of 'Sight & Sound', once referred to several of Hitchcock's plots as examples of 'madman's flytap'. I'm not sure where she got the term from, but this week I'll try and apply it (in a non-pejorative way ...) to Hitchcock's Rebecca. (Note. I'm not overlooking how the film's plot essentially comes from Daphne du Maurier's 1938 novel, a product of what Patricia White in her recent BFI Classics monograph on Rebecca, p. 99, calls its author's 'prodigious imagination'.) Consider this. When a woman's body had been found, washed up on a lonely beach, Maxim - who may have killed Rebecca (he does so in the novel) - is able to mis-identify the body as Rebecca's. How convenient for him! Rebecca had been proficient at sailing boats, but her boat had disappeared along with Rebecca herself, and the assumption at the original inquest was that she had died at sea. Later, after marrying 'I', Maxim tells his new bride that Rebecca had stumbled in the boathouse, where Maxim had confronted her about her extra-marital affairs, and (in the film) had hit her head on a piece of ship's tackle. Maxim explains to 'I' that the body on the beach had been that of an unknown woman, 'unclaimed, belonging nowhere'. That body, then, washed up shortly after Rebecca's disappearance, was also very convenient for the book and film's plot! But later, after Maxim re-marries, Rebecca's boat is unexpectedly found at the bottom of the sea by a diver. A new inquest is called. This time, Maxim has more explaining to do. Initially, he states that he must simply have mis-identified the body on the beach. However, also called to testify at the inquest is the boatbuilder Tabbs, and he has a dramatic line: 'There's them 'oles!' He is referring to holes punched in the bottom of Rebecca's boat from the inside. However, again conveniently for Maxim, the new evidence can still be read as indicating suicide. But why would Rebecca have done that? The last section of the book/film provides a - convenient! - answer. A London doctor (Leo G. Carroll) is found who testifies that Rebecca had been suffering from an irreversible cancer. Maxim confides to 'I' that Rebecca, in the boathouse, knowing she hadn't long to live, had deliberately tried to goad him into killing her - which would have meant that his own life would be placed in jeopardy if he were found guilty of her murder! (What a lovely nature she didn't have, despite her 'beauty, brains, and beauty'!) Already, that's quite a lot of plot invented by du Maurier's 'prodigious imagination'. But, further, what about Maxim's explanation of all this to 'I'? Did Rebecca really fall and hit her head in the boathouse? It sounds an unlikely story. Although the screenplay couldn't have Rebecca murdered and then Maxim not found out - by the rigid rules of the American Legion of Decency for all films (decreeing that a culprit of a major crime must be punished) - Hitchcock was able to bring considerable ambiguity to Maxim's account of what had happened. He tells 'I' that he had buried the body at sea and then scuttled the boat, ostensibly to prevent scandal, and/or to avoid suspicion of murder falling on him. (As noted, in the novel he does kill Rebecca.) But note. In the film, we only have his word that he didn't kill Rebecca. His explanation to 'I' in the boathouse is perhaps the film's most powerful scene. A tour de force. (Patricia White, p. 90, notes that here Hitchcock opted 'for heterotopia rather than flashback', meaning that the scene works by invoking spaces that are somehow 'other' ...) But rather than just accept that Maxim had simply disposed of the body to prevent scandal, maybe we are free to infer additional details, not spoken. For example, did Maxim's feelings of guilt - after all, he had 'hated' Rebecca - cause him to panic? And maybe he is lying - he did kill Rebecca. Certainly the plot of Rebecca is ingenious, as I have claimed. Finally, as I've mentioned Patricia White's monograph, let me add a final note this time. I was struck by White's comment (p. 82) that 'Rebecca's aura seems to form a forcefield' that surrounds 'I'. That word 'forcefield' is exactly what I was trying to convey last time (July 17, above) when I referred to how our early view of Manderley through the windscreen of Maxim's car makes Manderley seem to 'have a visible spell cast over it'. (See frame-capture below.)

July 17 - 2021

These days I read the film Rebecca as a comedy in the very best sense - it feels meaningful and rings true. The comic note never feels cheap (see last time). For one thing, iit is impressively character-based. I think of how the timid 'I' is as much initially frightened of Mrs Danvers as she feels lost in Manderley's maze of corridors. However, well before the end, she has grown up - the perennial theme of so many Hitchcock movies over the years. (When Maxim attends a new inquest near the end of the film to explain the holes in Rebecca's boat, his young wife is there to give him her full support. See frame-capture below.) (I see the theme as almost inevitable, given such a masterful director.) Early on, Mrs Van Hopper (Florence Bates) is the main comic character: 'Hurry up, don't dawdle', she orders the hapless 'I' in a loud voice that tells us she is used to ordering her paid companion around and expects instant attention. In turn, 'I' squirms with embarrassment when her employer acts over-familiarly towards Maxim in the Monte Carlo hotel foyer. 'I' is probably as much embarrassed for Maxim as for herself - but Maxim soon shows that he is very capable of sizing up Mrs Van Hopper and administering a snub in double-quick time, before walking off. However, he already knows 'I' from the opening scene on a clifftop, and undoubtedly has noticed her embarrassment now - and has been taken by it. Not long afterwards, he encounters 'I' alone in the hotel foyer and invites her to join him for a drive. Now comes another subtle piece of characterisation. In his own way, the aristocratic Maxim is as much - or more - used to getting his own way without question as Mrs Van Hopper: we can infer that his late wife, Rebecca, who we hear was 'fearless', may have offended him for reasons he never admits. (At the climax, of course. he tells the startled 'I', 'I hated her!', i.e., Rebecca.) Specific incidents confirm Maxim's own arrogance. For example, in the car, he suddenly brakes and tells 'I' that if she doubts him she had better get out of the car and walk! Topping that is his proposal a bit later: 'I'm asking you to marry me, you little fool!' They get married in a registry office. He buys her some flowers. In the following scene, they are driving through the Cornish countryside towards Manderley (I don't think they've had a honeymoon), but the moment is not exactly auspicious. It begins to rain. (Echoes of the rainy wedding-day in Hitchcock's first film, The Pleasure Garden.) Stopping the car, Maxin points out to his bride the distant manor that is Manderley. Framed through the car's windscreen, it appears to have a visible spell cast over it. We see it as forbidding and apart. Now, back to the matter of Rebecca's comedy. Something that Mrs Danvers may remind us of is how Hitchcock was fond of depicting butch women for their 'entertainment' value. I think too of the novelist Isobel Sedbusk (Auriol Lee) in Suspicion (1942). Isobel is by no means disagreeable, but certainly masterful like Hitchcock himself - indeed, he sees fit to give her a knowledge of plotting, and of true-life murder cases, to rival his own. In Rebecca, there is also Beatrice Lacy (Gladys Cooper), Maxim's plain-spoken sister, who, fortunately for 'I', takes an immediate liking to the new bride. Beatrice is married to Major Giles Lacy (Nigel Bruce), seemingly a bit of a duffer, revealed in the novel to have been one of Rebecca's victims, i.e., seduced by her. Giles and Beatrice's marriage appears childless - there are no children in Rebecca. (I commented on this at the end of last week's entry, above.) More next time.

July 10 - 2021

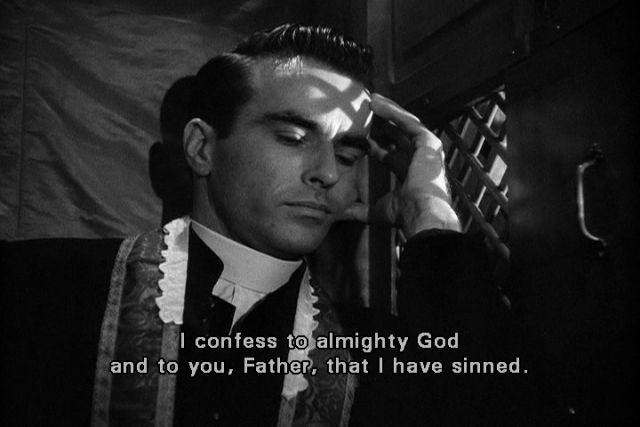

Another change of topic, as I'm currently writing about Rebecca (1940). I have always admired it, but I'm now of the opinion that it is one of the Master's very best films. This, after producer David Selznick had taught him a thing or two. Notably, Selznick considered Hitchcock's intention to open the film with a scene of seasickness (cf Champagne, 1927) was 'cheap beyond words' and insisted that the scene be dropped - surely for the better. For a long time, the 'enfant terrible' of British filmmaking and then its top director, Hitchcock had gone virtually unrivalled in his own country. However, his admiration of Hollywood's production values was very high. His arrival to live and work in the American industry gave him exactly the extra discipline that he probably needed. Just before leaving England, he had made a limp film of Daphne du Maurier's 'Jamaica Inn'; Selznick now assured the author that he would not permit her best-selling 'Rebecca' to be mistreated that way. 'It is my intention to do Rebecca and not some botched up semi-original.' Probably its most interesting character is, of course, the sinister housekeeper Mrs Danvers (Judith Anderson). (See frame-capture below.) After Maxim (Laurence Olivier) brings his new bride, 'I', (Joan Fontaine) back to his ancestral estate, Manderley, she is immediately terrified by the hostility of the older woman, who clearly had, and still has, a 'thing' about Maxim's first wife, Rebecca - who supposedly drowned at sea. Note: it isn't clear how 'Mrs' Danvers acquired her title. Anyone less likely to be married (to a man, that is) is hard to picture. Presumably, the 'Mrs' is a courtesy title given to her when she came to Manderley as Rebecca's personal assistant. We're soon told that she 'simply adored' Rebecca. Mrs Danvers's probably lesbian - or 'butch' - nature is thus established from the start. So, too, is her single-minded devotion to Rebecca's memory, and 'Danny's' unrelenting hostility to the woman who has taken Rebecca's place. ('Danny' was Rebecca's name for Mrs Danvers, and Maxim unthinkingly sometimes still uses it - he is initially unaware of how 'I' is oppressed by the strange housekeeper.) At one of the film's many climaxes, Mrs Danvers tries to persuade 'I' to jump to her death from Rebecca's bedroom window ('Go on! It's easy! Why don't you?), only to be thwarted by rockets suddenly fired at sea to signal that a ship has run aground. Rebecca sustains its melodrama throughout, and that is not a criticism but rather a tribute to the story's tight plotting and countless unexpected twists. (Incidentally, speaking of wicked housekeepers, such characters were not unprecedented in fiction - I also think of the 'wicked' witches in the fiction of L. Frank Baum! I seem to recall that Hitchcock himself thought of some of his female villains as witches.) Hitchcock boasted to François Truffaut that he had tried to avoid 'humanising' Mrs Danvers by dressing her in black and seldom showing her moving. And indeed, he seems to have based the character on another, called Mrs Unthank, in the novel 'The Great Impersonation' (1920) by espionage writer E. Phillips Oppenheim. Here's how Oppenheim introduces his malevolent housekeeper: 'A woman whose advent had been unperceived, but who had evidently issued from one of the recesses in the hall, stood suddenly before them all. She was as thin as a lath, dressed in severe black.' And here, for comparison, is how du Maurier introduces Mrs Danvers: 'Someone advanced from the sea of faces, someone tall and gaunt, dressed in deep black ...' (Hitchcock told Truffaut that he found du Maurier 'derivative'!) Understandably, the type has continued in movies: think of the devastating housekeeper, Mrs Baylock, in The Omen (Clive Donner, 1976). Another oppressive element in Rebecca is the fact that all of Manderley's menfolk seem 'impotent' and denatured. (Even the younger Frith at the gatehouse is elderly. His father is the oldest of Manderley's house staff.) Typical is a remark made about the estate's resident eccentric, 'Barmy' Ben, that he's 'perfectly harmless'. The person who makes that remark is the estate-manager, Frank Crawley (Reginald Denny), a bachelor, whom Maxin calls 'as fussy as an old mother hen'. As for the marriage of Maxim and 'I', it soon becomes one of 'companionship', a mere extension of 'I's' previous employment with the overbearing Mrs Van Hopper. Not incidentally, a suppressed final chapter to Daphne du Maurier's novel, unpublished until 1981, reveals that the central couple are still childless several years later. To be continued.

June 26 - 2021

Hitchcock's first feature film, The Pleasure Garden (1926), which we started talking about last week, seems to have some careless things in it that can't readily be attributed to the incomplete prints that are going around on DVD. For instance, several times we are told by the intertitles that the film's second half takes place 'out East'. (And indeed this section of the original novel is set in Burma.) And yet, when the villainous Levett writes to his new wife Patsy, reporting that he is ill, the address at the top of the page is North West Africa (more precisely a town there named 'Lakar', which seems to be a fictitious name). That's scarcely 'out East', I would think! I wonder if the young Hitch even noticed the slip, if that's what it is, or whether he was rushing to make his next film The Mountain Eagle, of which no prints now seem to exist. I infer that Hitch only gradually gained the total control that he exercised - and prided himself on - later. Nonetheless, commentators have noticed that in the opening credits of The Pleasure Garden he was already signing his name with a flourish. Inference: to be a master filmmaker, you must think yourself a master filmmaker! And already Hitch's eye for the telling detail was evident, certainly. Hmm. George Orwell noted that the author Charles Dickens filled his novels with 'unnecessary detail', which became a mark of his expansive style. Hitchcock, by contrast, certainly paid attention to details (most of the time) but they were typically pared-down details. When the good-hearted Mr Sidey, Patsy's landlord, climbs on a chair to reach the topmost shelf of the kitchen sideboard, where there's an old biscuit tin containing money (which he is prepared to give Patsy so that she may rush to her husband), he breaks a few plates as he reaches up. That detail emphasises the special effort he is making. I was reminded of the telling close-up in The Birds of broken cups hanging from hooks on a sideboard, betraying that a swarm of birds have invaded the house overnight. (The house is that of Mrs Brenner's neighbour. She will shortly find him dead in his bedroom, his eyes pecked out.) Something else I would note about The Pleasure Garden is its sustained atmosphere of near-licentiousness, in keeping with the opening scenes in the Pleasure Garden Theatre. All those high-kicking chorines, for one thing! The theatre owner, Hamilton, seems to consider them his personal chattels - at one moment during a reheasal he comes onstage and handles one of the girls, and seems to think nothing of it. (Oh well, that's show business, perhaps?!) Nonetheless, as noted last time, he seems to also like (or prefer?) the attentions of his male couturier, whom we see with an arm draped around Hamilton's shoulder. Hitchcock, an entertainer as well as realist, was of course happy to show this side of things, though he would steer his film towards a happy ending in which the decent Hugh marries the good Patsy and together they return to London at the end, with marriage on the cards. 'Give 'em what they want!' was always Hitchcock's working credo, which included always giving us a happy ending (of sorts) as well as a few glimpses of forbidden behaviours and things. He was also an expert at manipulating our attitudes, of course. I think of a moment when Levett has set his intentions on marrying Patsy - primarily to have sex with her - and approaches her from behind, in the street. Just for a moment, Patsy is unaware of him. We see a shadow of Levett loom on a wall, and then, next minute, he is tapping her on the shoulder. The shadow tells us something, albeit it may be subconscious for now. I recall that Hitch would use a similar technique in Foreign Correspondent to characterise the duplicitous Fisher (Herbert Marshall) and undercut his smooth exterior. (Frame-capture from The Pleasure Garden below shows Jill on left, and Patsy.) More next time.

June 19 - 2021

Reader, we may come back to The Trouble With Harry - it deserves plenty of attention. (Note. I have written an article on it for Geoff Gardner's Film Alert 101 website. It's now up.) Meanwhile, my work has taken me back to Hitchcock's first feature film, The Pleasure Garden (1926), which has always been highly watchable. The good news is that since 2012 there has been a restored print of the film, with up to 20 minutes of extra footage, done by the British Film Institute; the bad news is that so far it hasm't been released on DVD. So my own viewing has had to be a composite of watching two different prints: the earlier restoration by the same organisation - and actually shown on Australian television a few years ago (naturally I made myself a copy) - and the so-called Rohauer print that was distributed commercially for a while by Raymond Rohauer. Each print has differences. One of the differences seems to be that the Rohauer print has more footage of the fussy male couturier who works for the Pleasure Garden Theatre's manager, Mr Hamilton. In my book I wrote: '[the] butterfly-like male couturier ... has been sitting alongside Hamilton on a sofa, with an arm around his shoulder. It's a pre-echo of Vandamm's chummy friendship with his male secretary Leonard, seen decades later in North by Northwest'. That's fair comment, I think. And now look at the frame-capture below. It shows chorus-girl Jill (Carmelita Geraghty) paying money to the same couturier; this, straight after refusing to help her friend Patsy (Virginia Valli), also a chorus girl, with her fare in order to rush to her husband, reportedly ill 'out East'. What a striking image! The fellow is positively creepy, wringing his hands in anticipation, and one leg rubbing the other - he's a regular Uriah Heep! Mind, Patsy's husband proves to be the film's real villain. He's played by top English actor of the day, Miles Mander, and his name is Levett. His principal reason for marrying Patsy appears to be that he wants to have sex with her. This seems confirmed by the novel on which the film is based (it's written by 'Oliver Sandys' - a woman) when it has him say: 'Women were put into the world for us. There's nothing in it. P'raps I've never had a conscience. Shouldn't know what to do with it if I had.' (Chapter XLVII) No sooner is he far away from Patsy, now his wife, than he begins an affair with a native girl - who pins all her hopes on him for a better life and in the end will be mercilessly drowned by him: he's been driven mad after Patsy turns up and finds him in flagrante delicto with the girl. So, yes, The Pleasure Garden is a melodrama, but one full of cleverly-written and cleverly-directed moments. One of the ambitious Jill's 'moves' is to take a fiancé, Hugh (John Stuart), principally for the convenience of the arrangement. The trouble is, in her view: he isn't rich. Early in the film, Patsy invites Jill to board with her because Jill has been robbed of her purse, and has no money. Jill gratefully accepts. We see Patsy pay off the taxi driver. Alone together, Jill shows Patsy a photo of Hugh - and promptly yawns. The moment is ambiguous. Was that yawn just a sign of tiredness? Or has Jill betrayed her true feelings - or lack of them - for Hugh? Hitchcock allows us to interpret the moment as we see fit. The two girls do quickly retire to bed together, as there is only one bed. Another ambiguity now arises. Do we detect 'sapphic overtones', as Hitchcock biographer Patrick McGilligan has called them? Frankly, I don't (in the prints I've seen) - but I must be wrong! Asked about this scene, Hitchcock said that it was inspired by a lesbian couple whom he had encountered in Berlin in 1924 when, up to that moment, he had been innocent about such matters. Believe it or not, the couple got into bed together in front of not just Hitchcock but other onlookers, including a young female student, who 'put on her glasses to make sure she wouldn't miss anything'. That bespectacled young woman strikes me as a recurrent character in Hitchcock movies - although not necessarily played by Patricia Hitchcock. More next time.

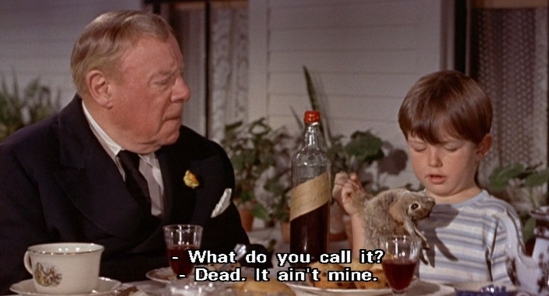

June 12 - 2021

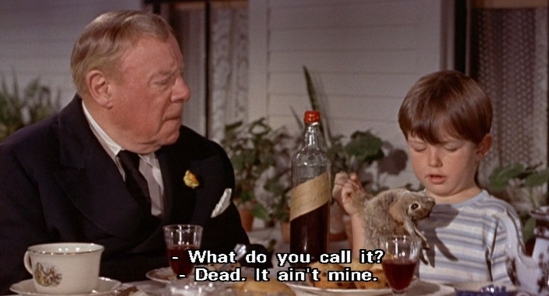

Before we start on this week's item about The Trouble With Harry, let me just mention that my article on Rear Window - expanded from some recent thoughts here - is getting hundreds of 'likes' on Geoff Gardner's Film Alert 101 website, which is something not happening when I post here! Hmm. Immodestly perhaps, I've always believed the adage, 'Build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door' - but I'm guessing that was coined before the days of FaceBook. Am I right in supposing that FaceBook is almost essential if you want to reach a large audience on the Internet these days? (For several years before FaceBook, this site drew many hundreds of weekly readers. I can't believe that a serious interest in Hitchcock, with or without a boost from academic courses on his films, has dwindled markedly in these times.) And again immodestly, I think that my detailed analyses of Hitchcock have, by and large, got more perceptive rather than less so! Any feedback that readers care to offer me will be read with interest and gratitude! Now, somewhat arbitrarily, I'll resume my observations about Harry by talking further about young Arnie (frame-capture above). Someone has suggested that most of us, in our lifetimes, move from a state of innocence to one of innocence-lost to one of innocence-regained. (They were writing about the art and poems of mystic William Blake, 1757-1827.) Arnie still dwells in his original innocence, but may have already begun to lose that innocence after his encounter with Harry, the film's MacGuffin and symbol. Arnie is just at the age where the Oedipal crisis sets in, and where the child learns that, for all the world's bountiful nature, it requires decisions that will limit (or delimit) him. You have to admire his direct answer when asked about the rabbit he has found (seemingly shot by Captain Wiles). To the well-meaning but condescending adult's question from Miss Graveley, 'What do you call it?', Arnie answers bluntly, 'Dead!' (See frame-capture below. Arnie could of course have answered with a name like 'Roger', which would have been what Ivy expected to hear.) That same bluntness is what Hitchcock's comedy is offering us, and thereby, perhaps, pointing our own consciousness towards innocence-regained. Full marks to Hitchcock the artist, who seems to have already attained that enviable state of mind and its state of awareness! William Blake does in fact figure in the English novel on which Harry is based. There, when the story's artist Sam first comes into view, he is singing the song 'Jerusalem' whose words are taken from a famous Blake poem: 'And did those feet in ancient time/ Walk upon England's mountains green ...' Those lines both establish a 'pastoral' (or Arcadian - see last time) mood and imply an allegory about Christ. On the whole, though, the allegory is played down in favour of the mood - and Hitchcock understandably follows suit. The 'look' of Harry with its autumnal russets and golds is what most people bring away from it, albeit we subliminally associate that look, and that mood, with the 'blessing' Harry's characters - and, by extension, its audience - are being given. Like a parent, Hitchcock is happy to tease us, knowing that reminders of our vulnerability will only engage us the more. The film's running gag about the yawning closet door in Jennifer's house as the conspirators hurry to dress Harry for his final burial works like that, even as it offers a refinement to the allegory: seen aright, there is literally nothing to fear. (August Strindberg's expressionist A Dream Play, 1907, contains a practically identical trope, as I recall.)

June 5 - 2021

The best theoretical lesson that I remember about comedy and the comic principle was the one I received from a lady schoolteacher in an English class. 'Comedy', she said, 'always involves something that is incongruous.' She pointed out that if you or I slip on a banana skin, it isn't particularly funny. But if a self-important gentleman in a top hat slips on a banana skin, that is funny (especially if the context permits us to laugh: for example, if we're only watching a movie anyway, without having a personal tie to the person). Alfred Hitchcock's comedy The Trouble With Harry (1955), from the short novel by Jack Trevor Story, is built on the two principles of incongruity and impersonality. We can laugh at the dead Harry's indignities of being buried and dug up multiple times just because he is only the dead body, the corpse, of a person whom we never knew (although in life he sounds to have been a real heel) and because all of this takes place in 'Arcadia', namely, rural Vermont in the Fall, with its autumnal colours (all underlined by the gloriously mellifluous and variegated music of Bernard Herrmann). Our attitude to Harry is epitomised by Jennifer Rogers (Shirley MacLaine), who had been briefly married to him, when she tells artist Sam Marlowe (John Forsythe) what he can do with Harry: 'You can stuff him and put him in a glass case, for all I care ... only, I suggest frosted glass!' And Harry's unfitness to be here in Arcadia is spelt out by Sam when he talks of 'City people ... people with hats on ... little people'. Arcadia, then, is not congruous with the City! In other Hitchcock films, of course, Hitchcock shows affection for city people, such as the apartment-dwellers in Rear Window. Each film is a subjective world, neither more nor less. I was shocked to read that Thelma Ritter, who played the sharp-tongued Stella in Rear Window, actually turned down the part of Miss Gravely in Harry (ultimately given to Mildred Natwick) because she considered that film 'immoral'. Her actual words, in a letter to her husband, were: 'I must not have much vision but this one scares me. It's lewd, immoral, and for anyone without a real nasty off beat sense of humor, in very bad taste.' Nonsense, Thelma! You are confusing immorality with sheer comic amorality, which may be more honest than morality, let's face it! In a Hitchcock film, nothing is finally determinate. For example, I used to think of the absent-minded Dr Greenbow (Dwight Marfield) in Harry as just a convenient deus ex machina figure, and that his final pronouncement that Harry died of 'natural causes' was simply a convenient way of ending the film - with a collective sigh of relief. (Interestingly, the play on which Hitchcock's 1929 film Blackmail was based did end that way.) In fact, though, there is no reason to take Dr Greenbow's word as definitive. It would be typical of Hitchcock to leave the matter up in the air, posing a barely discernible question ('So what is the real truth of the matter?') hanging. That's what I call profound! All right, let's move to other aspects of Harry. I like how, as in Rear Window, it offers us a whole cross-section of people, from the youngest, four-year-old Arnie Rogers (Jerry Mathers) toting his plastic gun through the trees and meadows (see frame-capture below), to the oldest, the middle-aged Miss Gravely and Captain Wiles (Edmund Gwenn, in his fourth Hitchcock film) and the widowed Mrs Wiggs (Mildred Dunnock), mother of the local Deputy Sheriff Cavin Wiggs (Royal Dano). Calvin is an 'enforcer' figure, and his name suitably suggests both 'Silent Cal' Coolidge (thirtieth President of the United States, said to be a do-nothing President) and one of the founders of Puritanism, John Calvin. Well, Harry is certainly not pro-Puritanism, and possibly it was ahead of its time, or just more English than American, when it came out in the 1950s. Perhaps that explains Thelma Ritter's confusion. Hitchcock thought Harry embodied his own sense of humour, and was sadly disappointed when it flopped at the box-office - except in Paris (of course!) where it ran for six months. More next time.

May 29 - 2021

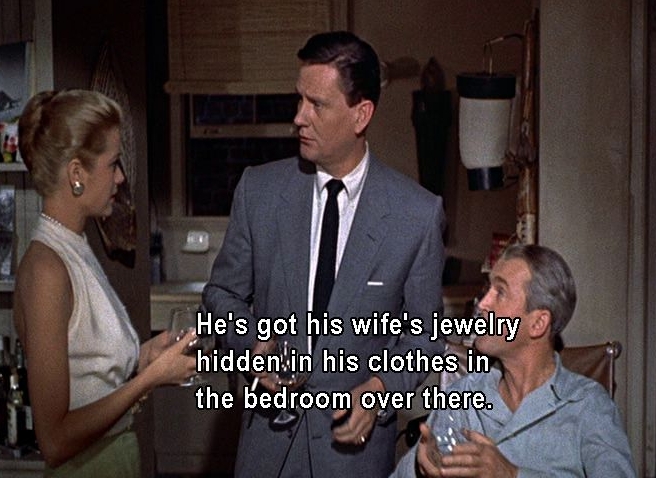

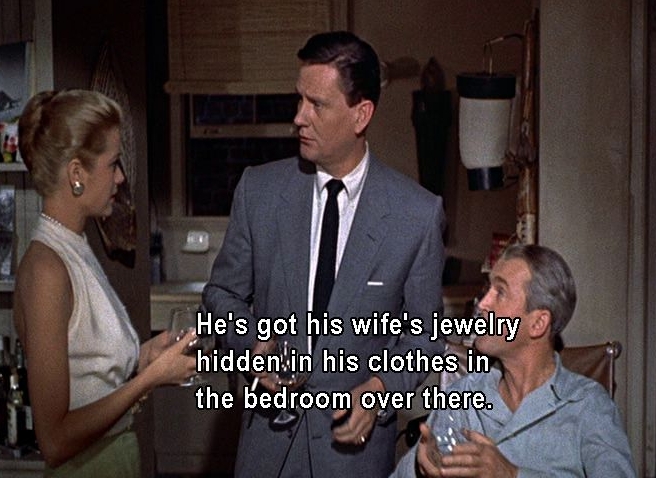

A beauty of Rear Window (1954) is how everything becomes part of a fluid, flowing whole, all seemingly with minimal implausability - until you think about it. And even then ... After all, Hitchcock knew that life is a bit of a jumble. And he had done his homework. So he knew that murderers have killed their nagging wives (e.g., the Major Armstrong case at Hay-on-Wye in the 1920s) and that they have cut their victims up with knife and saw and kept the remains in places like a hatbox and a biscuit tin (the Patrick Mahon case, also in the '20s). So don't despond, Hitchcock lovers! The Master knew what he was doing! Sometimes Hitchcock covers an implausibility with a line of dialogue, although he usually tried to further cover it with circumstantial detail. Detective Doyle tells Jeff that Lars Thorwald would hardly have killed his nagging, bed-ridden wife (cf frame-capture, below) in front of an open window, and then cut up the body afterwards, and now be walking calmly around the apartment, to which Jeff responds, 'That's just where he's being clever!' That line serves to fob off the 'plausibilists' in Hitchcock's audience, especially as we didn't actually see the murder - only heard a woman's brief scream and then the sound of a glass breaking. (However, we learn later that Thorwald strangled her.) Besides, Hitchcock's audiences invariably wanted 'something to happen' (and were seldom disappointed) - meaning that those audiences easily felt that they were already 'accomplices'. The bottom line is that Hitchcock didn't care excessively about making everything in his film plausible, so long as it kept the flow going. The doubting Doyle manages to track down the trunk that Thorwald had shipped out of his apartment the morning after Mrs Thorwald disappeared (Patrick Mahon also used a trunk to help him dispose of the remains of Emily Kaye ...), although this detail proves to be either a red herring or a Hitchcock joke - take your pick. Jeff and Lisa wait breathlessly to hear what Doyle had found, and Doyle answers, 'Mrs Thorwald's clothes.' Moreover, a woman calling herself 'Mrs Thorwald' had been seen arriving at the trunk's destination. So the flow of information is maintained, despite another implausibility which Hitchcock no doubt trusted that no-one would notice (or anyway quickly forget about). That trunk had been tightly tied up with rope which looks to us viewers that, if it were cut, the tampering would be obvious. I surmise that Doyle used his police badge to have the rope cut or untied - but surely the false Mrs Thorwald would have quickly conveyed such information back to Thorwald! (A near-identical implausibility occurs a couple of years later in the 'Alfred Hitchcock Presents' episode called "Guilty Witness" from AHP's First Season. Incidentally, two years after that, in Vertigo, Scottie has left the police force but kept his badge - which he uses to get information from the lady at the McKittrick Hotel. Hitchcock never forgot that a plot-device often bears repeating!) Lastly, I'd like to mention a different matter in Rear Window: its 'friendly' attitude to Thorwald until he goes too far, and resorts to murder. After a fierce nagging one morning from his wife, this seemingly gentle man goes outside to prune his zinias. The script notes: 'He goes to a small patch of flowers, perhaps three foot square. They are beautiful ... He kneels down, inspects them, touches them affectionately and with some pride. His anger seems to have left him, replaced by the kind of peace that flowers bring many people. He stands up, carefully hoes the ground, then rakes it. Then he snips a few leaves of the lower parts of the plant. Finally, he waters them.' However, next minute the elderly lady with the hearing-aid, the Scuptress, leans over the fence and 'begins gesturing to him how to take care of his flowers'. You have to feel sorry for the poor man!

May 22 - 2021