Editor's Week 2018

December 29 - 2018

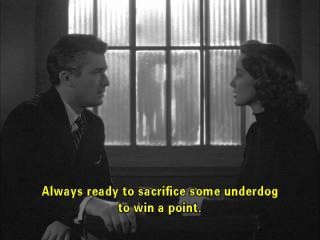

'Hitchcock invariably tried to respect his source material's themes'. I wrote that last time, and the point is further borne out by his rendition of Paul Bourde's 1902 melodrama 'Nos deux consciences'/'Our Two Consciences' into I Confess (1953). The play is newly translated into English by Morry C. Matson (no publisher given). In some ways, it feels quite different from the film - which, more than ever, I judge to be one of Hitchcock's finest - but nonetheless the basic structure is there. A parish priest, Father Pioux, in a French village, when accused of a murder, cannot defend himself, basically because of the inviolability of the confessional (the murderer's wife has confessed to him her suspicions of her husband, a carpenter at the presbytery) but also because the Father doesn't want to reveal a private matter concerning himself and one of his parishioners, the wife of his good friend, Dr Bordier. The investigating magistrate, Judge Dubois, has come into possession of letters from the murdered man, another priest, accusing Father Pioux of 'an inappropriate relationship' with a young woman - who will turn out to have once been involved with the priest's beloved brother. Both the brother and the resulting love-child have since died; moreover, the woman in question is Madame Bordier, who has never told her husband of what happened! Meanwhile, and fortuitously, the murdered man has been killed during a robbery that went wrong, his killer wearing a priest's cassock for disguise. It's a convoluted, yet still powerful, central situation, in an otherwise minor play (I would judge) - and the translation is not particularly helpful (some shoddy English). That said, the play can throw considerable light on the strengths of the film, which has taken the situation and enriched it admirably. For a start, the confession is put up-front and centre by Hitchcock (in the first few minutes of the film), and given not to the killer's wife but to the killer himself. Helpfully, too, and tying the various plots together, the murdered man is made to have been blackmailing the married woman whom he alleged to have once had relations with the film's priest (before the latter took holy orders, naturally). Reading the play, I was better able to see what the blackmailer was driving at - that the woman had never told her husband of the incident (nor, at the time, had she told the priest-to-be, just back from the War, that she had got married while he was away!). Clearly, there are three or four principal groups of characters in both play and film. The film's priest, working at a rectory in Quebec City (the only city in North America where in 1953 priests still wore cassocks in public places) is Father Michael Logan, played beautifully by Montgomery Clift; his counterpart in the film is the village priest Father Pioux. The Bordier couple in the play are the equivalent of the film's Ruth and Pierre Grandfort (Anne Baxter and Roger Dann). The poverty-stricken murderer and his wife, the Bressauds, in the play are the equivalent of the film's German refugee couple, the Kellers. (Otto Keller works as a sacristan and general helper at the rectory.) The play's investigating magistrate, Judge Dubois, is the equivalent of the film's Inspector Larrue (Karl Malden) who is a close colleague of the Crown Prosecutor (Briane Aherne) who happens to be a good friend of the Grandforts ... (Lately I have been wondering: shouldn't the Crown Prosecutor have recused himself from the Logan case, given that he is so close to two of its injured parties, the Grandforts?! Still, it does help the film's continuity!) Now, there is at least one big sequence in the film for which there is no real matching scene in the play, and that is the film's subjective flashback, essentially the romanticised memory of Ruth, pertaining to her affair with Michael Logan, before he went off to the War - something which, as he says in the film, changed him, and made him decide to take holy orders. For me, this is a stand-out part of the film, which is consistently rich and powerful in any case (whereas the play sometimes seems to me to become almost pedestrian). I'll have more to say about this and other matters next time. Meanwhile, below is a frame-capture from the start of Ruth's flashback: her (literally) glowing descent of the curved staircase seems to be a variant of a rather differently-inflected scene in Elia Kazan's A Streetcar Named Desire (1951)!

December 22 - 2018

I want to say a bit more about Mark Padilla's book 'Classical Myth in Alfred Hitchcock's Wrong Man and Grace Kelly Films' (2018). When I earlier reviewed David Sterritt's 'Simply Hitchcock' (also 2018), I said that I wished Sterritt had illustrated the actual mechanisms of some of Hitchcock's generalised 'truths' (see November 10, above). That's something that Padilla does well, and repeatedly, by situating the films in a 'classical' setting - what is called 'classical reception', defined by Padilla, p. xvii, as identifying 'classical markings on post antique materials'. For example, apropos To Catch a Thief, he illustrates the dynamics of its moral aspect by drawing parallels with ancient Greek myth and philosophy. (The original novel of TCaT, by David Dodge, is likewise a moral tale, noting that Francie has made Robie aware of 'the moral aspects of thievery' - Penguin edition, 1953, p. 97.) On the maturing relationship of Francie and Robie, Padilla at a couple of points invokes Plato's 'Symposium' with its reference to Diotima, a prophetess and philosopher, who taught how eros may lead to forms of enlightenment. (There's an amusing BBC Radio 4/Open University summary of 'Diotima's Ladder' on YouTube. It runs under 2 minutes.) Padilla puts the idea like this: 'Strong desire of a beautiful person should be encouraged in the person who wants to begin a philosophical pathway ... eros can lead to sophrosyne [self-regulation]'. (p. 320) Next, Padilla advances the idea by invoking another dialogue of Plato, the 'Phaedrus', which 'develops the iconic image of the philosopher's soul as a charioteer whose car is perilously pulled by two winged horses with opposite natures, one noble and rational, the other impulsive and irrational, but both necessary to reach a desired goal' (p. 326) (Many Hitchcock films, on analysis, show an appeal in roughly equal measure to their audiences' noble and irrational sides!) Finally, Padilla sums up: 'Robie and Francie are initially associated with Dionysus and Cupid, respectively so, and Francie's behavior projects a perversity that is troubling. However, through the narrative structure of the film and through its resonant vocabulary, each protagonist ethically evolves, and they accept more responsibility for the impact of their actions upon others, including each other. These themes accrue greater classicism from the shooting sets' inclusion of physical reminders of antiquity, especially architecture and statuary.' (pp. 333-34) Somewhere in there is the idea - touched on last time - that all of us are located on a continuum, which permits Hitchcock's audiences to identify, at some level, with the films' characters and their interactions. But there is a further, ambiguous dimension (which, pardoxically, probably only adds to the films' power to involve us). Padilla speaks of how TCaT 'conveys an ambivalent set of cultural values - ones that both criticize and embrace international "Dionysian" identity - [so that] the film tries to have its cake and eat it too as a metaphorical social critique'. (p. xxxvii) I'd like to take a cue from that observation to return to the passage from the novel quoted above, and which clearly influenced the filmmakers' adaptation (for Hitchcock invariably tried to respect his source material's themes). Here is more of that rather subversive passage (which particularly struck me after reading Padilla's analysis of the film) ... '[Robie and Francie] discussed moral distinctions all during the drive back to Cannes. [She] argued that a thief's only function was to steal, as the Monte Carlo's roulette wheels' only reason for existence was to win money for the Prince of Monaco, so that in the event John were to lose money at roulette and regain it by robbing the prince, no one could fairly say "good" or "bad" of either one, although in practice the Monegasque police would jail John and he could not jail the prince. [Robie] found it entertaining to listen to her serious analysis of the criminal's place in society.' (p. 97) (Frame-capture below: Robie at the Mone Carlo roulette wheel.) In somewhat the same fluid vein (and roughly consistent with what Padilla reported about the ending the screenplay originally had - see last time) is a passage from near the end of the novel in which Robie helps Danielle elude punishment. 'Afterwards he could not remember any conscious change of attitude in himself, from pursuer of a thief to the thief's ally. One identity had merged into another while he was both hunter and hunted [...] She was a thief, he was a thief. [Commissaire] Oriel threatened them both.' (p. 196) Was Hitchcock's ultimate morality, then, one of amorality?!

December 15 - 2018

Mark Padilla's chapter on To Catch a Thief (1955) is the first long analysis I have seen of the considerable classical imagery in that film, including the interior and exterior statuary at the Sanford Villa. About the latter, I had supposed no more than how the formal 'sedateness' of the statues serves to highlight the 'aliveness' of the characters, especially at the climactic gala costume ball, in which everyone - even policemen - must dress up for the occasion to resemble Marie Antoinette's court at Versailles. (Note: behind the credits of TCaT is a travel sign proclaiming, 'If you love life, you'll love France.' Life-against-death is a tangible motif of countless Hitchcock films: e.g., The Trouble With Harry.) By contrast, Padilla notes such things as the film's 'sets brimming with neoclassical architecture', 'images of Cupid [running] wild in the film's décor, both in inside and outside spaces', 'statue groups [that] suggest ... the film's symbolism [visually] ... Inside the [Sanford] courtyard, for example, noble visages comment ironically on the hedonism of the elite guests. Outside, on the villa grounds, Francie and Robie interact with statue groups in [a] way that speaks to their conversations and emerging relationships.' (p. xxxvi) (Below is a frame-capture from the ball scene showing the hosts receiving their 'elite' guests. Note the statue of a towering male figure behind them and, further back, two smaller statues of female figures.) Now, I had long felt that TCaT is something of a lightweight moral drama, in which, for example, Robie had been leading a rather sterile existence (raising flowers) until events - and Francie, in particular - had taught him that he 'needed the help of a woman'; but again Padilla has uncovered every nuance and interaction to show how 'three dimensional' the moral drama actually is. For example, drawing parallels with classical myth, he suggests that Robie is like a Dionysus-figure (the film's multiple references to theatricality and acting are noted, as when even Jessie Stevens and the insurance-agent Hughson play their 'parts' to fool the police at the gala ball) while, for much of the film, Francie and her mother spur Robie on, like 'maenads' (female followers of Bacchus) participating in 'the cults of Dionysus' (p. 303). Initially the widowed Jessie is the one who pursues Robie, attracted by his panache at the roulette game in the Monte Carlo Casino, but her actions awaken Francie's interest in Robie, especially when she learns of his criminal activities before the War. As Padilla puts it: 'Francie shows signs of perversity in the form of hybristophilia (sexual pleasure from being with criminals, a motif found elsewhere in Hitchcock)' (p. 284). (Cf "Editor's Week" for November 3, above.) In turn, this leads to Padilla's emphasis on the film's considerable use of 'mimetic desire' to drive its drama. The term 'mimetic desire' was made famous by René Girard (1923-2015) who built a grand theory of human dealings and interactions on it, almost as complex as Marxism. Padilla doesn't mention Girard by name, but he illuminates TCaT by showing several of its 'Girardian' aspects. He writes: 'Francie becomes the double victim of "mimetic desire," that is, eroticism that she inherits from two other females. One is her mother, Jessie, whose interest in Robie is transferred to her daughter. [...] Danielle also has erotic designs on Robie, but here Francie becomes her competitor, rather than her agent, and Danielle-the-thief strikes the Carlton Hotel, where the Stevenses are staying, the very night Francie seduces Robie, and this act of sabotage destabilizes Francie.' (p. xxxvii) Two observations. First, Girard did indeed show how readily rivalry and envy flow from mimetic desire, becoming driving forces themselves. Second, note that both Francie and Robie are 'destabilized', thus setting them on the path to moral growth - and in both cases Danielle, who is herself driven by envy of Robie's wealth, is the agent. It's small wonder that both the film and the original novel, by David Dodge, show considerable sympathy to Danielle. Padilla reminds us that in a draft of the screenplay Robie was going to visit Danielle in prison, 'promising to support her through the process' (p. 318). Robie would thus have made some atonement for not having shared his wealth with his Resistance colleagues, including Danielle's father. As it is, the film implies another of Hitchcock's (Dionysus's?) perennial motifs: how we're all actors in a vast drama. The gala ball climax has Robie saying, as he dangles the captured Danielle from the roof, that she must make her own form of atonement/confession: 'you've got a full house down there. Begin the performance.' More next time.

December 8 - 2018 (late)

It's that time of year, so apologies for no blog this time. I had been intending to keep on with The Birds, but now I have a couple of books in my sights to talk about, including Mark Padilla's challenging - and often insightful - 'Classical Myth in Alfred Hitchcock's Wrong Man and Grace Kelly Films' (Lexington Books, 2018). Its chapter on To Catch a Thief is long and informative, and I like Padilla's attempt to show the reader that '[f]emale mimetic desire is brilliantly played in a game of three-dimensional chess' (p. 318) - by Francie, her mother Mrs Stevens, and Danielle. Also, Padilla recognises how TCaT is a moral tale, and his elucidation of that aspect is praiseworthy! Next time, then. KM

December 1 - 2018

I recently had occasion to show an audience the classic trailer for The Birds (1963) in which Hitch delivers a 'little lecture' on man's (and, explicitly, woman's) treatment of our feathered friends down the ages. We don't exactly come out of it well, although Hitch pretends not to notice, even reminding us that 'the turkey is traditionally our guest at Thanksgiving'. Holding up an egg - a reference to battery farming (for 1963, the trailer is remarkably ahead of its time) - he expresses gratitude for the 'fantastic heights of egg production' that the caged hens achieve. And in the frame-capture below he is talking in glowing terms of 'the benefits of the shotgun' - the NRA could hardly have faulted what Hitch says here. (Cf also the "Bang, You're Dead!" episode of Alfred Hitchcock Presents.) In fact, of course, he is using the tongue-in-cheek technique pioneered by Jonathan Swift in his 'editorial' called 'A Modest Proposal For preventing the Children of Poor People From being a Burthen to Their Parents or Country, and For making them Beneficial to the Publick' (1729) - i.e., the technique of saying one thing and meaning practically its opposite! (In appearing to advocate a form of cannibalism, Swift was actually drawing attention to the plight of the starving Irish.) As I told my audience, the technique is one that Hitchcock used a lot in his television shows to 'have it both ways'. For example, he might appear to be siding with a murderer (say Barbara Bel Geddes in "Lamb to the Slaughter", who disposes of her two-timing husband), and can thus build up sympathy for someone who may be essentially only human and pushed to the limits of her/his endurance. At the same time, by a kind of 'reverse logic', we know what the 'moral' of the story is - in this case, that murderers have invariably 'gone too far' and the law says that they must be punished! Such a TV show is in effect doubly involving! Similarly, Hitch's apparent misanthropy in the trailer for The Birds works to build sympathy for the avians, and provide a 'motive' for them to attack humans in the film, while simultaneously that same 'misanthropy' - and the humorous tone of its presentation - 'bonds' us as we listen (and maybe even acknowledge our collective guilt!). In short, although Hitch in the trailer says he doesn't 'believe in dealing with controversial matters', we recognise the truth of what he says. That truth is very like what the philosopher Schopenhauer called the 'Will' in humans - a life force that is also a death force - and it's significant that we hear Hitch refer (with a shrug) to 'Nature's way [which] man simply hastens along when he can be of help'. Significantly, too, The Birds itself is probably the most overt of all Hitch's films to deal with Will, his most 'schematic' film that way. In 'The Alfred Hitchcock Story', I spell out the parallels. For example, I say that Will is 'typified by human egoism and rapaciousness. Understandably, Schopenhauer [...] considered Will to be a cruel joke, best turned against itself, notably with the help of art or music. The Birds is an almost literal enactment of that thought. As Mitch [Rod Taylor] leaves the pet shop, he says that it's time Melanie ['Tippi' Hedren] found herself "on the other end of a gag". He gets his wish - writ large.' And again: '[I]n The Birds, Hitchcock effectively confronts us with the Will that causes [human and animal] suffering. Schopenhauer characterised the Will as ultimate reality, not finally knowable, and the blind cause of suffering in the world. Allusions to blindness are everywhere in The Birds (e.g., the game of blindman's buff at the children's party; the farmer whose eyes are pecked out), and this is doubly appropriate, given both our own inability to know ultimate reality and the blind way that reality, Will, operates. The birds effectively symbolise Will.' Also, speaking of Hitch's 'bonding' us as we watch his films or TV shows (or his trailer for The Birds), it's interesting how 'representative' Melanie and the Brenner family become in the film. Towards the end, after the avians have been besieging the Brenner house, one shot brings everyone together. Three successive close-ups show the three principal characters rising into frame (Mrs Brenner in the middle), until we hear Mitch say, 'They're gone' - whereupon the camera pulls back to show all the characters together. (The attic scene, which follows, will show that bonding in operation.) QED. (Further reading: my long - bring a cut lunch! - much-commented-on (!) monograph about The Birds and its sources, published online in 'Senses of Cinema': Birds Synoptic Account.)

November 24 - 2018

I want to wind up my 'review' of David Sterritt's book 'Simply Hitchcock'. My point last time about Psycho and Frenzy is that Hitchcock's 'excremental vision' amounts to a perfectly valid - and unblinkered - understanding of how people are, and their place in the scheme of things. Such a vision doesn't annihilate a more aspirational - spiritual - side of our psyches. Not at all. And although the latter is always precarious, it's assuredly 'better' than the cant of the politician at the start of Frenzy, pontificating about the cleaned-up Thames, freed of 'effluent'. His reference to 'brown trout' is unfortunate - apparently that's slang for excrement. (That's something else I learnt from Ian Cooper's monograph on Frenzy, mentioned last time.) Next moment, a woman's body floats ashore. Even more unfortunate! Especially as the film's symbolism equates such things - women as victims of men's lust and even murder - with, again, waste and excrement. But, note, Hitchcock isn't saying that men are the ultimate villains. The villainous propensity is in the psyche - and where did that come from? Ah, there's the rub! Note that Sterritt, ex-film critic for the 'Christian Science Monitor', is one of several critics who feel that in Frenzy Hitchcock 'went too far'. The shot of the murdered Brenda Blaney - see last time - offends him. Hmm. All I know is that the shot is very close to a photo I once saw in a forensics textbook in a university law library, i.e., it's real(istic). And what is wrong with that? It isn't gratuitous, and the film is told/directed with all of Hitchcock's attention to meaningful content and, at the same time, artistry and taste. Another of my favourite quotes about the director is the tribute paid him by composer John Addison: 'He's the most civilised man I have ever met.' So now I'll come to a film whose estimation by Sterritt I can agree with - absolutely. 'Family Plot is mellow, cheerful, delightful', he wrote when reviewing it in 1976. His book is very perceptive about that film: 'I think [Hitchcock] regarded Family Plot as a sort of [quixotic] last stand against frailty, finality, and mortality ... looking for loopholes in the human condition was nothing new for Hitchcock, who disliked definitive conclusions ...' (p. 136) That's surely dead right, and I only wonder why Sterritt doesn't more consistently apply the insight throughout his book! (Frame-capture from Family Plot below: Barbara Harris as the fake medium Blanche - but how fake?!) Pity, too, about the little slips that punctuate the book. One slip is the same as that made by Peter Ackroyd in his little book on Hitch (2016): The 39 Steps (1935) doesn't end where it began (cf Sterritt, p. 50). The film begins with Mr Memory's act at a seedy music hall somewhere in East London; the fact that when we see him again, at the classy London Palladium, he has risen in the world, contributes to the pathos of his death, shot by the villains who had taken advantage of his (likely) financial vulnerability earlier, to bribe him to work for them. (Note: he is betrayed, too, by his other weakness, his inability to resist showing off his memorised knowledge when a member of the audience asks him a direct question. Other Hitchcock characters also perish because they lack the resilience of a Hitchcock hero: e.g., 'Beaky' Thwaite (Nigel Bruce) in Suspicion (1941), unable to resist a glass of brandy when it's offered to him socially.) And, speaking of Beaky, Sterritt is wrong to say that he 'spills gossip galore about Johnny's exceedingly chequered past' (p. 71). Rather, the thing about Beaky is that at their English school he had always 'worshipped' Johnny (that's Sterritt's spelling of the name) - he may have been his 'fag'. Beaky gushes uncritically rather than gossips about Johnny/Johnnie, as when he says that the latter 'can lie his way out of any situation'! Another Sterritt error - more than a slip this time, because he says it twice (e.g., p. 10) - is that in Psycho 'Norman ogles Marion in the shower'. No, he watches her undress in her cabin before she writes her note and does her figuring, then goes to take a shower. (Note: Hitchcock doesn't cheat. The fact that Marion spends time on the note and the figuring is presumably long enough for the aroused Norman to go back to the house and change into 'Mother's' clothes, then return ...) Another Sterritt slip is to say that in The Ring (1927) Jack's fiancée, played by Lilian Hall-Davis, is named Nelly and is the carnival snake-charmer (p. 29). In fact, her name is Mabel and she sells the tickets to Jack's boxing act from a booth at the entrance. (When did Sterritt last see The Ring?) Lastly, a couple of matters that irritate. Sterritt claims that Hitchcock wanted Tippi Hedren's first name to always be printed in quotes. That's only half-correct. They weren't double quotes (as the book keeps using) but single quotes - and Hitch insisted on them, emphasising their decorousness. Also, Sterritt repeats the fallacy (developed at length by, e.g., Stanley Cavell) that the title of North by Northwest (1959) is a quote from 'Hamlet'. Hitchcock and screenwriter Ernest Lehmann were mirthful when they read that. (See John Russell Taylor's 'Hitch', 1979.) Even so, thanks for your book, David Sterritt!

November 17 - 2018

Continuing my thoughts on David Sterritt's 'Simply Hitchcock' (2018), first I'll comment further on why I think the title of Rich and Strange (from 'The Tempest') is not only apt, and perceptive, but predictive of other Hitchcock films to come. Hitchcock, by the nature of his work, i.e., reading the minds of his audience and out-manoeuvring them (Hitchcock: 'I like films with plenty of psychology'), was understandably ambivalent about 'innocence'. As a Catholic, he admired it - even as he saw that it could be frightening, because it equated with 'ignorance'. But then, so are we all ignorant! In returning Fred and Em home safely, where they resume their bickering, Hitchcock as 'teller' of their story, is simply both 'sadder and wiser' than they are. In being drawn to travel in the first place (as a result of Fred inheriting money), and with their vision of 'the Orient' as something exotic, Fred and Em are only human - naive if not small-minded! Many of Hitchcock's films and TV shows are about the felt need of his characters to 'grow up'. Raymond Durgnat' added, 'a little' - which he meant as a put-down of the limited nature of the films' content. But that content has a universality to it. Early in Shadow of a Doubt (1943) young Charlie's state of mind resembles what the philosopher Kierkegaard called 'dread', a state of innocence or dreaming that awakens a thirst for the prodigious and the mysterious. (Cf also Vertigo!) Later, when she learns the truth about her uncle in the public library scene, the camera's upward retreat evokes The Fall. And when she confronts her uncle about her new knowledge (which Kierkegaard indicates is analogous of adolescent experience generally, and the acquisition of one's sexual identity - see 'The Concept of Dread'), Sterritt reminds us of what Uncle Charlie tells her: 'The world's a hell. What does it matter what happens in it?' Accordingly, Sterritt writes: 'This ranks with the most bone-chilling passages in all of Hitchcock's work ...' (p. 78) That's true of course - and can perhaps be put alongside the image in Frenzy (1972) of the strangled Brenda Blaney, who has died at the hands of another very sick serial-murderer, Bob Rusk (Barry Foster). That's an image described by Ian Cooper in his excellent 2018 monograph on Frenzy: 'A good contender for the nastiest shot in the Hitchcock oeuvre' (caption, p. 66). Not incidentally, Rusk is heard complaining at one point of his wanting to get away and travel - it's as if Hitchcock is implying that even murderers have a restlessness that is (again) universal, and potentially dangerous, and how to that degree we may all share the same basic instinct. An author who has perhaps written the most eloquently about such a restlessness, and who was inspired by Freud and Nietzsche (more importantly, who throws light on Hitchcock), is Norman O. Brown, who called the restlessness 'the universal neurosis of mankind', equivalent to 'the theological doctrine of original sin'. ('Life Against Death', Sphere Books pb, 1968, p. 18.) My reason for citing Brown will become more evident in a moment, but note the overlap with young Charlie's experience that gives her knowledge of The Fall even as it ends her innocence. Now, I'm trying to show that Sterritt goes a certain way, but no further. As I said last time, I would have liked some comment from him on the mechanisms of human frailty. I also said that his book is 'not always accurate', which is something I'll illustrate next time. Here, I want to comment on a part of his book where he obviously enjoyed himself! Writing on Psycho (1960), Sterritt is frank: 'I can't leave Psycho without touching on the most wickedly playful element of the whole playfully wicked film.' Picking up from his earlier Hitchcock book ('The Films of Alfred Hitchcock', 1993), he reminds us that Freud linked money and excrement, and that Psycho 'links cash, shit, and crime into a metaphorical chain that crisscrosses the entire story' (p. 121). Memorably, millionaire Cassidy waves a wad of what he calls his 'private money' in front of the real estate office staff, who all gasp. Why? 'Because in this film money = shit, and nice people don't wave it under other people's noses; they put it out of sight and out of mind, especially when there's so much of it.' (p. 121) The swamp at the Bates Motel is one large 'sewer' in a film that contains multiple lavatory references (as Raymond Durgnat was the first to note), and into which Norman (Tony Perkins) sinks the car (with its 'ANL' numberplate) containing both Marion's body and the stolen money - thereby becoming 'waste products' themselves. Etc. But Hitchcock was by no means the first artist to have an 'excremental vision'. Multiple literary critics from the 1960s up to the present have taken their cue from Freud, Norman O. Brown, et al., to write about such a vision in Jonathan Swift, Charles Dickens, James Joyce, and many others. More to the point, Sterritt seems oblivious of how Hitchcock's Frenzy takes the imagery a good deal further. For example, a woman's corpse mingles with a truck-load of potatoes (destined to be returned to the soil as 'waste') before being 'excreted' from the back of the truck when it brakes suddenly. (Frame-capture below.) To be concluded.

November 10 - 2018

Here are some more thoughts prompted by David Sterritt's new book 'Simply Hitchcock', which offers a guide for the keen 'beginner', or student, to Hitchcock and each of his 50+ films. If these thoughts constitute a 'review', so be it. My overall feeling is that the book is consistently perceptive if not always accurate and certainly not 'new' in the way that you can always hope a book - even an introductory text - might be! (Nor does it contain photos and frame stills, as at least one other book-length overview of Hitchcock does, to supplement its text.) A praiseworthy ingredient is Sterritt's repeated observation that Hitchcock regularly sees past the 'illusion, confusion, and misperception' of his characters and their representations. For example, Rear Window (1954): 'No film better illustrates Hitchcock's conviction that vision provides us with our most powerful knowledge of the world, yet is equally capable of leading us astray ...' (p. 103) I just wish that Sterritt would comment on the mechanisms of such human frailty. But he does show how the particular films go about instructing us. Of Hitchcock's 1944 short film Bon Voyage, we learn: '[It] centres on a Royal Air Force gunner [whose escape from a pow camp is engineered by the Gestapo to lead them to members of the Resistance]. The film then revisits his escape, which [now] looks very different [...] The ambiguities of this story - between virtue and villainly, reality and illusion - are thoroughly Hitchcockian.' (p. 81) So they are. So why does Sterritt find 'slightly strange' the title of Rich and Strange (1931) which of course comes from Shakespeare's highly poetic 'The Tempest' about characters shipwrecked (and transformed)? The title is, firstly, ironic: Hitchcock's shipwrecked couple, Fred and Em(ily) - see frame-capture below - once they return home, seem to have been changed not a whit! Second, Fred and Em are thereby made representative of how Hitchcock tended to see 'the moron masses' (Hitchcock's phrase, remembered by John Steinbeck from working with him on his other 'shipwreck' film, the 1944 Lifeboat). And not only those masses. It's as if the director had anticipated, in his own poetic way, the gist of Edward Said's powerful text 'Orientalism' (1978) about the West's generally patronizing representations of 'the Orient'! As I noted here a few weeks ago (October 20, above), my favourite description these days of Hitchcock is his wife's: 'He has the most balanced mind of anyone I've ever known.' And to appreciate the extent of the breadth and depth and balance of Hitchcock's mind, it is necessary to recognise how much poetry there is in his collected works. I'm not sure that Sterritt does that. Still, I admire this general assessment of the director that the book gives us at the start, and which comes close to what I'm talking about: 'The danger of being thrust from the everyday world into a chaos world [as Fred and Em are, when they're shipwrecked] was a philosophical issue of deep interest for the filmmaker. It was also a psychological and spiritual issue that stirred him to his bones [...] Creative work was his safety valve, and the ability to communicate his half-hidden fears in universally meaningful forms was his saving grace.' (p. 2) Note that Fred and Em are permitted to return to their relatively secure world at the film's end, as are, say, the folk from Santa Rosa at the end of Shadow of a Doubt (1943) who remain blithely unaware of the true nature of the serial killer, Uncle Charlie, who had lived in their midst - as indeed they seem almost unaware of the devastating war being waged in much of the rest of the world! Interestingly, Sterritt tells us that when actor James Stewart came back from the War, his new outlook - idealism, you could call it - made him feel that his previous acting in Hollywood romances and comedies, like Lubitsch's The Shop Around the Corner (1940) and Cukor's The Philadelphia Story (1940), 'was inexcusably frivolous in the complex and conflicted contemporary world [...] and Hitchcock was happy to accommodate him [by casting him in the serious Rope (1948)].' (p. 87) Earlier, Sterritt had summarised the 'wake-up' message of that film like this: 'The schoolmaster [Stewart] taught his students to toy with murderous ideas, and now he's shocked that they acted on what they learned.' (p. 7) Very true. And arguably Hitchcock even took advantage of the actor's new idealism (a quality that Hitchcock instinctively distrusted, as in another of his vehicles for Stewart, the 1958 Vertigo, about infatuation) by making his earnestness finally seem naive! A case of Hitchcock having it both ways, because human nature is never simple. Sterritt says of Vertigo that its motif of high and low allows 'an enormous range of meanings', including 'idealism and cynicism' (p. 12). Sterritt provides the material; the reader, with a bit of work, can take much from it. More next time.

November 3 - 2018

Our News item below, added this week, about the opening of the opera 'Marnie' in New York, refers to Mark Rutland's 'fetish' for a woman whom he knows to have committed various offences such as lying and robbery, and suggests that such a fetish is called 'hybristophilia'. (The usual illustration of this fetish cites the 'fan' mail sent to criminals in prison from infatuated women, sometimes proposing marriage.) That term was the nearest I could find to label Mark's condition. There is an entry on the Web about one person's 'lie fetish', where the person admits to being aroused by observing someone tell a lie to another person, but that's hardly a medical term. Nor does the label 'kleptolagnia' fit Mark, because it refers to someone who is aroused by committing a robbery, not by seeing it committed by someone else. Nonetheless, as Hitchcock was the first to admit, Mark Rutland does have a fetishistic or 'paraphilic' interest in Marnie. Hitchcock makes some fascinating comments to François Truffaut, in their famous interview, about Marnie in particular. Yes, that film shows 'a man [who] wants to go to bed with a thief because she is a thief ... Unfortunately the concept doesn't come across on the screen. It's not as effective as in Vertigo, where Jimmy Stewart's feeling for Kim Novak was clearly a fetishistic love.' (There, as someone once pointed out, citing a study by Sigmund Freud, the sexual attraction may be enhanced by the fact that the woman is already married to another man - which is what Scottie in Vertigo believes 'Madeleine' to be.) Mind, the woman must be sexually attractive from the outset. The person mentioned above with the 'lie fetish' says that he wouldn't have been aroused if the person telling the lie had not been pretty. Hitchcock reminds Truffaut that he established at the outset that Mark had spotted Marnie. When [Mark] learns that she's robbed the safe, he says 'Oh yes, the pretty girl with the legs...'. Another interesting thing about Marnie is that so many of the characters have kinks. Mark's sister-in-law, Lil, admits she's 'queer for liars'. (Given that she fancies the widowed Mark, is she here deliberately - or subconsciously - aligning her own 'fetish' with his?!) The senior Mr Rutland, a widower himself, who otherwise appears fairly sedentary, seems more than ordinarily drawn to horses (and the aristocratic lifestyle?), when he observes, 'The best thing for the inside of a man or a woman is the outside of a horse.' As for Marnie, who has several 'peculiarities', not the least of them her great love for her horse, Forio, her remark, 'Oh Forio, if you want to bite someone, bite me!', does sound a little 'off'! (And who knows what secret desires Mark's 'banking cousin', the myopic-looking 'Cousin Bob', harbours within?!) So often, with fetishes, they go hand-in-hand with wanting to be in control, or have power over the fetishised 'other'. Probably they may serve a compensatory function, or be a form of 'revenge' for something experienced long ago - as when the girl Marnie was excluded from her prostitute mother's bedroom whenever a client spent the night there. The bigger point is that we can all relate, at some level, with the need to feel in control. David Sterritt makes an astute observation in his new book, 'Simply Hitchcock', about the fetishes and phobias that 'appear and reappear throughout Hitchcock's body of work, sometimes subtly, sometimes not ... They often [form] patterns charged with great expressive force, as when the voyeurism theme connects with [Hitchcock's] penchant for putting the spectator in emotional cahoots with the villain. Never once have I seen viewers decorously avert their eyes when Norman ogles Marion in [her cabin] ... or Scottie snoops on Madeleine's peregrinations.' (p. 10) Mark Rutland's fetish initially places him in the position of one of the jungle predators his zoology studies have taught him to admire. But his studies are part of his self-aware drive to keep himself mentally and psychologically healthy. On his honeymoon cruise with Marnie, he instructs her in the ways of Madagascan flatid (leaf) bugs: 'to escape the eyes of hungry birds they live and die in the shape of a flower'. (There's an illustration below.) It's as if he were telling a cautionary parable directed against the 'herd mentality' that infects timid souls, like those that Friedrich Nietzsche contrasted with his exalted (and liberated) Übermensch. In the darkness of a cinema, watching a Hitchcock film, audiences (I believe) often sensed that the film was speaking to them in oblique ways, collectively and individually. Which, very likely, was the whole idea.

October 27 - 2018

Speaking of child actor Billy Mumy's performance in "Bang! You're Dead" (see last time), I was impressed by a detail like the 'swagger' Billy's character, Jackie, has on returning home, still clutching his uncle's loaded gun: a lengthy panning-shot follows him from the garden to the front door, and the young actor keeps it up all the way! You can tell Jackie's proud of his gun, and that he feels he's had a splendid time 'terrorising' unsuspecting customers in a supermarket. (One young supermarket assistant has a lucky escape when she pops a sweet in his mouth just as he is about to shoot her!) See frame-capture below. Correspondent DF had some interesting thoughts about Mumy and Hitchcock this week. He reminded me that for many viewers who grew up in North America in the 1960s Billy Mumy may be best-remembered for his role in the series 'Lost in Space' (as well as 'AHP' and 'Twilight Zone'). Mumy is still alive, still with us. DF notes: 'Certainly his career has been happily different from that of [another] brilliant child actor, Bobby Driscoll.' (Driscoll made several pics for Walt Disney, including the 1950 Treasure Island where he played Jim Hawkins. Sadly, he died in 1968, aged just 31.) And DF makes a wise comment about Hitchcock himself: '[He] was doubtless able to be fairly nasty at times - aren't we all? But I reckon that he was just like other directors. Surely no director has ever had the reputation of being just a "nice guy"!' Exactly, DF! Having to be 'nasty' (well, firm and able to impose his will) is almost a requirement of being a good director. It comes with the territory. John Ford authority Tag Gallagher was telling me recently about some of Ford's misbehaviour that way, although his worst 'offences' may have been when he 'went too far' when working with his regular company - which included actors like Ward Bond - who basically all admired and loved him. But back to Billy Mumy and that incident when Hitchcock took him aside, saying, 'Billy, if you don't stand still on your mark, I'll come and nail your feet to the floor and your blood will run out like milk!' (For the adult Mumy's account, see the URL included here last time.) As I said to my original correspondent, JC, about that incident, I think Billy's mother made a good point afterwards when she told her son, 'Mr Hitchcock is English!' - as if that sufficiently explained matters! And maybe it did! (JC thought that there was a bit of foreshadowing of Monty Python!) My own thoughts immediately ran to how Hitchcock had read several novels by Charles Dickens at school and how his home library in California contained Dickens's complete works, including some valuable first editions. Prompted by my recent re-reading of John Carey's superb book, 'The Violent Effigy: A Study of Dickens' Imagination' (1973), I cited, first, the case of the Fat Boy in 'Pickwick Papers' (who very possibly may have reminded Hitch of himself growing up!). That drily-conceived character is noted for his constant eating and for his droll delight in terrorising people (compare Hitchcock's deadpan expression!). One day, the Fat Boy is about to consume a meat pie when he notices young Mary, the housemaid, sitting opposite. He leans forward, knife in hand, and slowly enunciates: 'I say, how nice you look.' 'There was enough of the cannibal in the young gentleman's eyes', Dickens remarks, 'to render the compliment a double one.' However, Carey rightly points out that the very best embodiment of a violence in Dickens's writing that 'could also express his black and anarchic laughter' is the character of the malevolent dwarf, Quilp, in 'The Old Curiosity Shop'. For instance: 'He smokes pipes of hideous strength, and forces his guests to do the same, warning them that otherwise he will put [one] end in the fire and rub it red-hot on their tongues. He drinks boiling spirit, bubbling and hissing fiercely, straight from the saucepan. He pinches his wife black and blue, bites her, and keeps her in constant terror of the ingenious punishments he devises.' (Carey, pb edition, p. 25) Meanwhile, she worships him! And there's a whole lot more of such grim humour in Dickens - not altogether different from what I call Hitchcock's use of a kind of 'reverse psychology' to convey his meanings, notably in his appearances on the TV shows. I also think of how he called Psycho 'a comedy'. Well, it is and it isn't!

October 20 - 2018

After reading last week's item, a correspondent, JC, reminded me that not all of Hitch's child actors remembered him fondly - notably, Billy Mumy who was 7yo when Hitch directed him in "Bang, You're Dead!" (AHP, 1961). Mumy himself tells what happened when, with time running out to fit in one more shot for the day, Hitch came to him and whispered that he must stop moving about or else ... To read what Hitchcock threatened to do, watch the entertaining 9-minute interview with Mumy (talking directly to the camera): Mumy on Alfred Hitchcock Presents We discussed the interview in our Hitchcock discussion group this week. We noted, inter alia ... Mumy would have forgiven Hitch for scaring him, and quickly forgotten the matter, if, after shooting, when they had got their close-up, Hitch had simply winked at him and said, 'I didn't really mean what I said!' But not only didn't Hitch do that, Mumy thinks that he enjoyed himself and was pleased with himself for getting the shot in that way! Mumy has remembered the incident ever since. Mind you, when the boy told his mum what had happened, she dismissed it, saying, 'Oh Billy, Mr Hitchcock is English and they say things like that!' Also, Mumy recounts how, a year or so after the incident (maybe a bit later), he talked with Veronica Cartwright, who played the pre-pubescent sister of Mitch (Rod Taylor) in The Birds. Mumy told her how he thought Hitch was a horrible man. But her experience had been quite different. 'Oh no he isn't!' she responded! There are of course stories of Hitch throughout his life that allege how unpleasant he could be (some of his elaborate practical jokes in the 1920s and 1930s; his making advances to Tippi Hedren after a day's shooting on Marnie in 1964). But equally, there are many stories of his charm, his selective generosity (i.e., not just to anybody!), etc. I told JC that my favourite quote these days about Hitch is what his wife said about him in 1960: 'He has the most balanced mind of anyone I've ever known.' Hitch was human, with, yes, a dark side. As for that "Bang, You're Dead!" incident, I think it shows not just Hitch's single-mindedness when he was making a film (he was scathing about some of the extras on Frenzy who put a foot wrong, although he left it to the Assistant Director to reprimand them!) but - come on! - by using some 'child psychology' that day he demonstrated that a little bit of fear applied to young Billy may have been the best way of getting the shot before the child was whisked away by union regulations (and regulators). I'm reminded of Grimms' tales and their young readers - fear speaks an unmistakeable message to children, but they're mostly resilient about it afterwards! - and possibly the quick-thinking Hitch thought of the Grimms too! Also, note, I think Billy's mum was not altogether off the mark when she cited Hitch's Englishness! Hmm. No question about young Billy's talent as a child actor. Besides "Bang, You're Dead!", I have seen him in 'Twilight Zone'. Both times, he's been very good indeed! On our group, Adrian Schober (see last week) agreed, and told this story. 'While Mrs Mumy was quite dismissive of [what had happened that day], she had misgivings about [Billy] appearing in the memorable Twilight Zone episode, "Long Distance Call" (aired earlier in the same year). As he remembers, "My mom almost didn’t want me to do it, she says. I wasn’t aware of that at the time, but I [found out] later on that because [the boy in the episode attempts] to kill himself in several ways, she was just very anxious about that, and she almost said she wasn’t going to [let me] do it ..." Like "Bang! You’re Dead,” it’s a remarkable performance from the child actor.' Readers, any further thoughts?

October 13 - 2018

Thanks for joining me again! Just a couple of short items this time. First, there's an interesting Alfred Hitchcock site started recently by someone in Australia (good place to be!). His name is Brent, and his site is called 'Brenton Film: the past, present and future of film', with a page headed 'Alfred Hitchcock Collectors' Guide'. For it, Brent has assembled valuable information to assist people seeking the best Blu-ray, DVD or digital releases of Hitchcock movies. Go here: Hitch Collectors Guide

Second, there's a new book that some of my readers may want to seek out, especially if they're interested in Hitch's TV work (both the episodes he directed himself and those directed by others but still recognisably carrying the Hitchcock 'brand'). It's co-edited by Debbie Olson and (my friend) Adrian Schober for Routledge, and is called 'Children, Youth, and American Television'. The first chapter is by yours truly, and is called "Recognizing the Children in Alfred Hitchcock Presents and the Alfred Hitchcock Hour". I'm going to quote here the first part of the chapter's Preface (hope you like it - I'll maybe expand on it here nest time): 'Sociologist Nick Lee observed: "In order to properly recognize children, researchers must make a firm decision not to apply the dominant framework." In other words, to see children and childhood for what they really are, it is necessary to think outside the customary frame. (Lee's point, to be taken up later, is that society hasn't always encouraged such a liberal outlook.) What this essay calls Hitchcock's "ecumenical" view, meaning his open-mindedness, is well-suited to such a recognition of children, and mostly that viewpoint informs the various episodes of the TV series, whether directed by Hitchcock or by someone else (such as Robert Stevens or Norman Lloyd). This essay also concerns itself with Hitchcock's long-standing interest in the "growing-up process" - including sometimes its reversal or annulment - which for him may have had its roots in English novels and plays and was no doubt sharpened when he began to feel himself an accomplished artist, especially of "suspense" pictures. Critic Raymond Durgnat noted the mechanics of that suspense, if not its broader implications, when he wrote of Hitchcock's audience: "He catches us in that semi-serious, semi-infantile area where we accept innocent and wicked as real moral states, and then insists that we grow up, a little." To be fair, Hitchcock's ostensible subject-matter is often like the famous MacGuffin: the artist's true intent may remain hidden until, with all distractions finally off the table, the characters, and the audience, face an elusive truth.' (p. 23) (The chapter deals at length with such AHP episodes as "The Crystal Trench", "Santa Claus and the Tenth Avenue Kid", and "The Schartz-Metterklume Method"; and such AHH episodes as "The Magic Shop" and "Where the Woodbine Twineth". Special attention is given to Hitchcock's appearances in the various shows' 'wraparounds', i.e., the often jokey and sardonic opening and closing segments. Also, Hitchcock's own work in the cinema is referred to, notably The Trouble With Harry. There's more information about the book on Amazon.)

Note: I was unable to find any posts from July to September in Ken's documents. The Wayback Machine Archive is also empty for this period. It appears that Ken was not active over this time. [AF]

June 30 - 2018

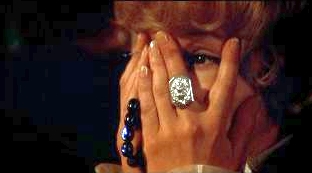

Back to Suspicion in a moment. But first, as a film scholar (and a sympathetic student of yoga and Buddhism), I have always been wary of how logic can seemingly be twisted to mean whatever you want to prove or to see, rather than allow the still(ed) mind to show you 'things as they really are'. In a recent book on Vertigo (one of several), by Robert J. Belton, he warns the reader against 'confirmation bias' but admits that he will probably be guilty of it himself. I think he's right about that! Here, for example, is something he says about the scene in Midge's San Francisco apartment where she, a commercial artist, is working at her drawing-board on the illustration of a new brassiere 'based on the principle of the cantilever bridge': 'Obviously enough, a suspension bridge hangs from cables, as a conventional brassiere does from straps. Filtered through this [...] understanding, Midge's description of the brassiere is not comparing it to the Golden Gate but to a kind of device that facilitates rather than threatens phallic rigidity. Scottie illustrates this with the deliberate, almost aggressive, way he points his cane at the brassiere. The castration threat is not just the fact that he wears a corset (i.e., a masculine substitute bra) but the fact that the doctors will ask Scottie to get rid of his corset the following day. Only then will he be in danger of losing his sexual potency.' (p. 62) While I appreciate the detailed description here, I wonder at the conclusion. Hasn't Scottie already symbolically lost his potency, as signalled by his wearing the corset (usually thought of as a female garment), and its removal tomorrow will represent a chance to become potent again? (Note: he needed the corset after hanging limply from a rooftop for what must have seemed an eternity. More symbolism there, notice! Compare the adventurous Jeff's situation in Rear Window where he is confined to his apartment with a broken leg and a wheelchair, the latter something usually associated with the elderly.) I may come back to this. Meanwhile, let's return to Suspicion. As I've noted again recently, I hope to soon publish on this site scholar and author Michael Walker's thoughtful piece on Hitchcock's 1941 film. On the topic of the director's penchant for sexual symbolism, Walker writes: 'An old friend [of Johnnie's], Beaky [Nigel Bruce] serves to highlight both Johnnie's immaturity and his potency. On the one hand, he and Johnnie behave like overgrown schoolboys together; on the other, Beaky is an emasculated buffoon: in one scene, Johnnie mockingly gives him a walking stick. The anecdote Beaky begins to tell of his failure to understand that the woman who picked him up in Paris was a prostitute - and his death from an excess of brandy in a Paris 'house' - further emphasise that he's a sexual innocent or, as Theodore Price argues, that he's gay [...].' (Price's book is 'Hitchcock and Homosexuality', 1992, re-titled 'Superbitch!' for its limited 2011 re-issue. Review here: Obsession with Jack the Ripper .) (For a frame-still of Beaky with Lina, see below.) Finally, as I'm quoting a lot this week, I'd like to briefly comment on my observation last time, comparing the ending that Hitchcock wanted for Suspicion with a Wagnerian love-death. Wagner described the ending of 'Tristan and Isolde' like this: 'The exhausted heart [of Isolde] sinks back, to pine away in a longing that can never attain its end, since each attainment brings in its wake only renewed desire, till in final exhaustion the breaking eye catches a glimpse of the attainment of the highest bliss - the bliss of dying, of ceasing to be [...] Here, I suggest, is an instance of why Hitchcock's films can often be called 'Schopenhauerian' (after the philosopher who influenced both Wagner and Nietzsche - and note that Hitchcock once described Wagner as his favourite composer). The first part of the above quote is pure Schopenhauer: repeatedly that thinker drew attention to how we are all prone to constant restlessness for, no sooner is one desire attained or eliminated, than another takes its place. (I would argue that the 'open-endedness' of Vertigo, et al., implies no less.) Moreover, referring now to the rest of that quote from Wagner, I suggest that this is another Hitchcock paradigm, akin to Schopenhauer's concept that the only release from our constant restlessness and 'suffering' caused by the world's 'Will' is to 'suspend' it in ourselves, as in meditation or the contemplation of great art. (Wagner had a whole concept of musical 'suspension'.) Last week, too, I quoted, apropos Vertigo, Nietzsche's famous aphorism: 'Whatever is done out of love takes place beyond good and evil.' Is that the message of both Suspicion and Vertigo? (Hmm. Reader, did you think you were just watching a suspense movie!)

June 23 - 2018

Some more stream-of-consciousness (or association-of-ideas) observations about Suspicion. I'll try and link them up with last time's. For instance, I suggested that while the ending Hitchcock wanted would not have been 'exactly a "Tristan and Isolde" love-death', it would have been 'quite close'! (Lina, out of love, would have allowed herself to be poisoned by her husband, while Johnnie - the ambiguous hero-villain - would have proceeded unwittingly to his own execution, because of an incriminating note Lina had given him to post.) Of course, whether the couple would then have been re-united in death isn't raised. That's for an audience to imagine, if it wishes! But the fact is that Lina and Johnnie's relationship has been erotically charged, as signalled by such things as the scene on the hill, early in the piece, which - again ambiguously - is filmed to resemble a murder attempt but proves to be Johnnie's attempt to kiss Lina! He immediately follows it up with an attempt to touch her 'ucipital mapilary' (I'm told there's no such thing!): compare the frame-capture below in which Johnnie proceeds to tease Lina about her hair which, he alleges, is 'all wrong'. Johnnie's pursuit of Lina continues until, at the Hunt Ball, he again whisks her away, in his car this time. As they drive past Lina's house, she innocently (?) asks, 'Shall we go inside for a drink, or something?', an offer which Johnnie politely turns down, imagining that Lina will insist. When she doesn't, he has to think quickly - which is Johnnie's forté! - and accept after all! The point is, the film is signalling that a romance is in the air. Lina never forgets the initial excitement of the incident on the hill. It is referred to several times during the film. Near the end, at another erotic moment - when Johnnie starts to undress Lina for bed - she resists, and Johnnie remarks, 'This reminds me of the day we first met - on top of the hill - when you wouldn't let me unbutton your blouse. Remember?' And Lina says, 'I'll never forget it.' The whole film is one continual tease, but with a tone that belies the depth of its 'love story'! It is teasing at various levels. In a way, I'm reminded of William Rothman's recent remark about Vertigo: 'Hitchcock has gone to extraordinary lengths to make Scottie's so-called dream sequence demonstrate that the world on film is not reality but a projection of reality, and that as a projection it is at once real and unreal.' Mutatis mutandis, those 'extraordinary lengths' are prefigured in Suspicion. Let's come back to the love story aspect. Of course it's 'unreal' - at one level. No film with so much 'joking' and switching back and forth could possibly be taken 'seriously', could it?! And when Lina finally 'gives up' and surrenders to Johnnie's murderous intent - which had so aroused her from the very start - that's from sheer exhaustion, isn't it?! In the screenplay, Lina mutters a final prayer: 'Oh, God, let him do it quickly. I can't stand it any longer. I don't want to live any more. There's so little strength left in me [...] And, please God, have mercy on his soul [...] He doesn't hate me, God - he's like a small boy [...]' Hmm. Richard Wagner described the ending of his opera 'Tristan and Isolde' like this: 'The exhausted heart [of Isolde] sinks back, to pine away in a longing that can never attain its end, since each attainment brings in its wake only renewed desire, till in final exhaustion the breaking eye catches a glimpse of the attainment of the highest bliss - the bliss of dying, of ceasing to be [...]' Reader, I did say that I'm sharing here some associations-of-ideas. I do feel that Suspicion has a dimension that is seldom recognised. Returning to 'Tristan and Isolde', I note that in the 2006 film of that name, Tristan dies in Isolde's arms with these words: 'You were right. I don't know if life is greater than death. But love was more than either.' That is very Hitchcockian. And Nietzschean. Writing on Vertigo, Robert Pippin invokes Nietzsche's famous aphorism: 'Whatever is done out of love takes place beyond good and evil.' Pippin explains that this has little to do with morality. Rather, 'Nietzsche is out to show something quite relevant to Hitchcock's movie. He wants to point out [ultimately] our inability in complex cases to distinguish among over-determined motives the relevant one.' A final thought, for now. Have others reading this ever felt that Johnnie prefigures Uncle Charlie in Shadow of a Doubt? I recall that when I first saw that film, it wasn't until deep into it that I conceded that Uncle Charlie must indeed be a murderer! For more than half the film, I felt that he might yet turn out not to be a murderer, that we were being given only circumstantial evidence and suspicion! And I never entirely felt that he was hateful.

June 16 - 2018

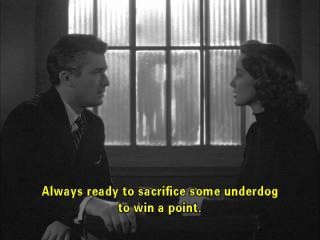

In a sense Suspicion is a highly modified version of the 'Francis Iles' novel, which offers a much more extreme situation (in its details, at least) than the film can do (given censorship and what 1940s film audiences would accept - although full marks to Hitchcock and his principal screenwriter, Samson Raphaelson, for striking the outlandish tone of the film, emulating the novel's). The novel is able to draw more closely on the real-life case of William Palmer (see last two entries). On the other hand, the best the film can do is subtly hint. For example, last week I noted how William Palmer had umpteen illegitimate children: at least fourteen! Taking its cue from this, the novel makes Johnnie seduce a succession of maids, and father a child by at least one of them. In an elaborate analysis of Suspicion ('Modern Language Notes', December 1983), M.C. Miller astutely noted a piece of dialogue in the film. He spotted an 'innocent' exchange, overheard by Lina, between Johnnie and the maid Ethel (Heather Angel) as she wakes him one morning after bringing the morning tea and post. (Note: yet another 'mail' reference by the film - see June 2, above.) 'Hello!' Johnnie says groggily. 'You here again?' (What were he and Ethel up to last night?!) Now, here are some almost stream-of-consciousness observations about Suspicion which I may follow up later. The film, as I say, is often subtle. Although Hitchcock told Truffaut that he would have preferred to follow the novel and have Johnnie kill Lina at the end, he finally realised that this wouldn't work with audiences. (Apparently such an ending was filmed, and shown at a preview, but the audience overwhelmingly rejected it. Hitchcock doesn't mention that detail to Truffaut.) Instead, he filmed the ending as we have it, in which at the last moment Lina sees that Johnnie wasn't prepared to kill her - that he was a loving husband - although Johnnie himself admits that he has done many bad things, that he's 'no good'. With a musical flourish, Johnnie agrees to reverse the car and take Lina back home after she had wanted to run away to Mother's. Ostensibly, this is a happy ending, and the couple can make a fresh start. In fact, it is - I would argue - deliberately 'sentimental' and unconvincing (not unlike the ending of The Lodger nearly twenty years before), and in any case is ambiguous. Moments earlier, Johnnie had appeared to try and thrust Lina from the speeding car, only she had managed to extricate herself. Whereupon he had quickly lied that he had been trying to save her! And almost immediately, Lina is heard saying, 'Oh Johnnie, I have wronged you ... please take me home!' (See frame-capture below.) Once again, I suggest, Hitchcock is being subtle with the truth! We are perfectly entitled to think, given all that has gone before, that Johnnie will try again to kill Lina when they are back home. His ready explanation that because of his 'badness' he had thought of committing suicide won't wash! That is, except with the ever-gullible Lina! This is one more instance of what Beaky had said, 'Good old Johnnie - always able to lie his way out of any situation.' Now, let's consider the ending that Hitchcock said he would have preferred. The general feeling of many critics and scholars is that it would indeed not have worked. As Michael Walker says in a powerful piece we'll publish here soon, 'Lina ... is our identification figure from early on. An audience would inevitably reject an ending in which she was killed.' However, that's not the whole story. Hitchcock explained to Truffaut that Lina would finally realise that Johnnie wanted to poison her - and, out of her own love for him, she was prepared to die (with the twist that to protect society from Johnnie in the future she would give him an incriminating letter to post!). Not exactly a 'Tristan and Isolde' love-death, but quite close! Remember that in Vertigo (1958) Hitchcock makes Judy do something similar: she is prepared to 'walk into danger' out of her love for Scottie, and does indeed pay the ultimate penalty for her love. Still, Walker may be correct in saying of Suspicion: 'finding a way of making the novel's sado-masochistic murder-cum-suicide acceptable to an audience was an insoluble problem.' But I have my doubts! More next time.

June 9 - 2018

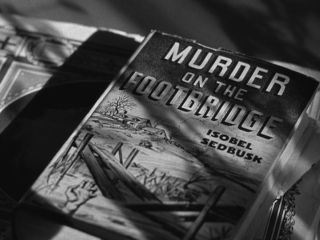

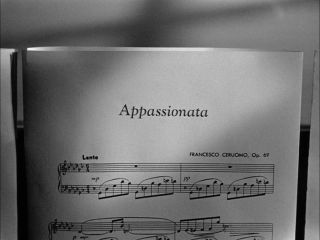

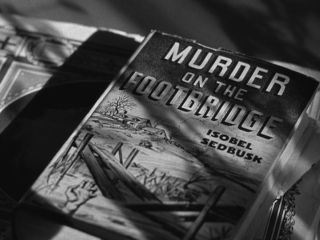

In Suspicion, the shadows grow more ominous and pronounced as Lina feels increasingly isolated from Johnnie (compare frame-capture last time). After he rebukes her sharply for 'interfering' in his real-estate idea in which the ill-fated Beaky will put up the money, the shadows are very noticeable. And of course, near the end, when Johnnie mounts the stairs to her bedroom (after switching off the kitchen light) and brings her a glass of milk on a tray, the shadows thrown by the moonlight are sinister. (Lina and Johnnie's waltz plays in a slow, dirge-like register.) The milk, we believe, contains poison. This follows the revelation, in the preceding scene, that Johnnie has found out an 'untraceable' poison. His informant had been the crime novelist Isobel Sedbusk who is the area's celebrity and whose brother is a forensic pathologist. Recently, Johnnie has become a 'fan' of Isobel, borrowing from her the true-life crime book, 'The Trial of Richard Palmer' (the film has changed the person's name from William Palmer - see last time), and buying her latest novel, 'Murder on the Footbridge'. Thus the film has done its 'homework'. Isobel is an Agatha Christie- or Dorothy Sayers-like figure. Interestingly, the film implies that she may be a lesbian. In one scene, in which Lina visits her, she is photographed leaning towards Lina and with her arm extended as if to place it on her thigh! She is charming towards Lina, and invites her and Johnnie to dinner in her cottage where among the other diners is a mannishly-dressed young woman of about Lina's age. According to the screenplay, this is 'Phyllis Swinghurst, who is staying with Isobel'. (In lines omitted from the film, Isobel calls her 'Phil', and she responds, 'Yes, Issie?') Isobel has at her fingertips, so to speak, all the details of the mass-poisoner William (or Richard) Palmer. He is the evident basis for several of Johnnie's traits, and for details of the film's plot. According to Colin Wilson and Pat Pitman's 'Encyclopedia of Murder' (1961), Palmer left school at 17 and moved to Liverpool (which is where Johnnie says his solicitors are located). 'In Liverpool, he quickly became acquainted with all kinds of crooks associated with racing. Soon, he left [his employers] under a cloud, having stolen money addressed to the firm.' In the next five years he had fourteen illegitimate children! At the age of 21 he inherited about £9,000. His first poisoning victim 'was a man named Abbey, whom he poisoned one day with strychnine in a glass of brandy simply to see how the poison worked. No suspicion was aroused by Abbey's death.' Palmer moved for a time to London. Incredibly, he gained himself a doctor's diploma. (This was in the 1840s.) He then moved back to his home town of Rugely in Staffordshire, where he ran up big gambling debts. He started poisoning his creditors. One of his victims was named Bly. Palmer owed him £800. The dying man managed to tell his wife of the debt before he died, but when she asked Palmer for it, he replied that Bly had owed him the £800, and that he would be obliged if the widow would produce the money! (In Suspicion, as noted last time, Beaky is impressed by how Johnnie could always 'lie his way out of any situation'.) 'Palmer now decided to extend operations to his family; he started with his uncle, "Beau" Bentley, another drunken profligate. Palmer proposed a brandy drinking match; the result was the same as in the case of Abbey; Uncle Bentley died within three days.' Palmer then married the daughter of a colonel in the Indian Army, presumably for the large dowry she brought him. It was her undoing. 'He insured his wife's life for £13,000, and then waited until the autumn; but by then, his creditors were clamorous, and Annie Palmer's life ended in September. Palmer put up an admirable show as a bereaved husband [...]'. Reader you get the general idea. Eventually, after he had poisoned the racing fan named Cook (see last time), Palmer was charged with murder. He was tried at the Old Bailey in 1856, found guilty, and executed at Stafford. Now, let's return to Suspicion and the crime novelist Isobel Sedbusk. The frame-capture below shows her latest novel, which Johnnie buys in order to meet her and presumably to obtain information about 'the perfect murder'. Note the hand of the drowning man after he has fallen from a tampered-with footbridge. (I'm sure that this was a murder method that other crime novelists had made use of. A variant on it is used in Hitchcock's Shadow of a Doubt, of course.) More next time.

June 2 - 2018

This week I received an email from ZP saying that he has 'a crush on Joan Fontaine' whom he likes 'very much in [Hitchcock's] Rebecca and in [Max] Ophuls' Letter From An Unknown Woman', and asking this question about Suspicion (1941): 'How are Joan and Cary [Grant] affording their lavish lifestyle after their marriage?' In reply, I noted, inter alia, that the novel by 'Francis Iles' (Chapter III) reveals that Lina's father had paid off Johnnie's debts and settled an annuity on his daughter of £1,000 (which the film changes to just £500 - all the more reason for Johnnie to take drastic measures when finances become really tight!). And, of course, Johnnie has all along specialised in borrowing large sums of money from the aristocratic friends in whose circle he has customarily moved. (Quite the lifestyle if one can manage it!) Now, speaking of drastic measures, I long ago noted in my Hitchcock book that the character of Johnnie is based on one of the most 'fascinating of real-life British criminals, William Palmer (1824-56)'. For example, Johnnie's resort to killing his rich chum 'Beaky' (Nigel Bruce) with a lethal glass of brandy echoes Palmer's resort, more than once, to poisoning wealthy relatives and friends (some of whom must have had weak hearts) whom he either challenged to a brandy-drinking match or administered a pill containing strychnine and with a glass of brandy to wash it down. (The body of one of his victims reportedly 'became so convulsed that his head touched his heels, and he died a few minutes later'. As Arbogast says in Psycho: 'Strychnine ... ugly way to die.') More on the parallels between Johnnie and William Palmer another time. Meanwhile, apropos Suspicion, I see that I noted here a few weeks ago (April 28) this: 'I used to think that the eminently facetious tone of North by Northwest (1959) had no real precedent in Hitchcock, but now I see that Strangers on a Train is its forerunner!' To that short list of films I might now add a few other titles, including Suspicion. Again and again, the plot takes an unexpected turn, zigging and zagging, in a way that is quite unreal by any normal expectation - but of course the mendacious, quick-witted Johnnie is no normal character. (Compare what I have said here about how Strangers on a Train takes its licence from the outlandish character of Bruno.) In a way, ZP's question above reflects Lina's sense that 'this can't be happening' - and yet the film insists that it is happening and (like Johnnie) manages to come up with an explanation! Also, maybe what happens in Suspicion is more life-like than we care to admit, only it is magnified. Practically all the film's major characters tell lies of one sort or another. Lina's mother (Dame May Whitty) tells a white lie when she placates her irascible husband at the dinner table by saying, 'But of course the horse-radish sauce isn't out of a bottle, dear' (both the novel and the screenplay make clear that she is fibbing!). Lina herself is soon telling lies (she has to be a fast-learner, once she comes under Johnnie's sway!), as when, on eloping, she tells her parents, 'I'm just going down to the village to post a letter.' Beaky lies when he says, on his first visit to Lina and Johnnie's house, 'I was just in the neighbourhood.' (Beaky can't conceal his admiration of Johnnie, whom he has known since they were at school together: 'Good old Johnnie - always able to lie his way out of any situation.') The film is one big lie about just how nefarious Johnnie really is: this isn't revealed until the last scene (in the ending Hitchcock wanted) in which Johnnie poisons Lina (but will be caught because of a letter that Lina has written). The very texture of the film creates a world of doubt and ever-increasing suspicion about what is really happening. As part of this texture, Hitchcock uses foreshadowings. In my book I noted the many 'postal' references that would have led the audience to that final scene: in the opening scene, Johnnie, caught out by a railways inspector, borrows a postage stamp from Lina to help him pay for his first-class ticket (he had purchased only a third-class ticket). The pillar-box in the village is repeatedly emphasised: Hitchcock even makes his cameo appearance there, posting a letter. Another instance of the way the film carefully builds its effects is related to the use of shadows that gradually increase inside the house, threatening to envelop Lina in her suspicions. Earlier, she had torn up a letter to Johnnie saying that she was leaving him. A proleptic shadow, almost like the bar of a prison, falls across her as she resigns herself to staying on. (See frame-capture below.) More next time.

May 26 - 2018

As promised last time, here are some final observations on the use of rear-projection and a model when the merry-go-round crashes in Strangers on a Train. First, in the frame-capture below, you can see the moment when the merry-go-round comes to a shuddering halt and one of the wooden horses appears to fly towards the camera. But look more closely. First, the bottom of the rear-projection screen is visible at the level of the policeman's shoulder. And note that the careering wooden horse disappears out of sight at the bottom of the rear-projection screen - although the effect when watching the film is of its crashing into the spectators in the foreground! But that's not all. After the crash, Hitchcock continues to use rear-projection, this time behind the screaming spectators as in the background we see Guy, holding his head, being helped away from the wreckage. Here, Guy is back-projected. But now there's a cut to a close-up of Guy, still holding his head, and here he is part of the live foreground - while rear-projection continues in the background to show milling spectators. And again, soon the camera moves to show Bruno lying injured on the ground - this is live action - while rear-projection shows other victims of the crash being helped away. In all of this, Hitchcock is doing exactly what he is supposed to do: direct not only the action of the actors but, very subtly, where the film's audience looks and what information it is given along with a sense of that information's relative importance. Now, the scene with the (presumably) dying Bruno is beautifully done. Especially notable is how he remains the character we have known all along, steadfast in his self-vindication even while cunningly trying to pin the blame for Miriam's death on Guy. (This anticipates the end of Psycho in which 'Mother' asserts her own rightness while putting the blame for the murders on her 'bad' son, Norman. Or is Norman exonerating himself and leaving Mother to take the rap? It's hard to know!) 'They got you at last, huh, Guy?' smiles Bruno grimly. His apparent single-mindedness is perfectly in keeping with what has gone before, even though we know that he's a psychopath and dangerously two-faced! (His 'single-mindedness' had been seen earlier in such things as his fixed stare at Guy playing tennis while all the surrounding spectators had swivelled their heads to follow the back-and-forth flight of the ball; or his unrelenting grip on Mrs Cunningham's throat at the party when Barbara in the background, with her resemblance to the dead Miriam, had caught his eye.) As I suggested at the outset of these notes on Strangers on a Train, it's a film whose style is determined by the outlandish nature of its subject matter and by the one-in-a-million character of Bruno himself - and therein lies its fun. Of course there are some wildly improbable moments within the action. Think of, say, Bruno's plan to have Guy kill his father, in which he waits in his father's bed when he suspects that Guy is going to double-cross him. Clearly, he could have got himself shot if Guy had indeed intended to go through with the supposed deal (as he does in the novel). But of course the whole story is improbable, isn't it?! And nobody knew this more than Hitchcock! It was his licence to create a tale where seemingly anything goes, always in keeping with Bruno's plan to harness the life-force or to fly on the first rocket to the moon!

May 19 - 2018