Editor's Week 2014

December 27 - 2014

[Our thoughts on Hitchcock's Suspicion resume next time. Meanwhile, Happy New Year to all our readers. K.M.]

December 20 - 2014

'Suspicion is a movie that is structured, from start to finish, around the cultural image [Cary] Grant's image represented; its suspense does not come from whether "Johnnie" (the character) could possibly be a murderer, but if Cary Grant could possibly be a murderer.' (Lesley L. Coffin, 'Hitchcock's Stars', 2014, pp. 31-32) This interesting statement may be very true - but let's never forget that Hitchcock's films are ultimately about the amoral life/death 'force' that one philosopher called 'Will' (in humans). Cary Grant, better than almost any other actor, can represent that amoral Will, and Suspicion is a 'surreal' depiction of a world seemingly governed by Will, although one part of us hopes that finally world and Will will be reconciled. The English setting of Suspicion is ideal, for it brings out in a clear-cut way the struggle of 'civilisation' against untamed spirit. Notice that from the opening moment on the train Johnnie is an anti-Establishment figure: throughout the film he will fall foul of authority and its representatives, many of them in uniform, starting with the railway ticket inspector. (Other such figures include General McLaidlaw, Captain Melbeck, and of course the police.) Strictly speaking, Will will always be with us - and part of us is grateful for that - so that ending a film like Suspicion was always going to be difficult. It could perhaps only be satisfactorily achieved by an act of love. (That is also the message of a film like The Birds.) Unfortunately the ending Hitchcock wanted - in which Lina (Joan Fontaine) sacrifices both herself and Johnnie - proved unacceptable to contemporary audiences, conditioned to expect that Cary Grant must finally 'grow up' and be proven 'good'. (The motif of 'growing up' - becoming civilised and accepting compromise - versus 'not growing up', is a perennial one in Hitchcock's films, going back to The Lodger.) Another ending the filmmakers thought of was for Johnnie himself to finally don uniform and to redeem himself in the RAF: I'm not sure whether this timely ending was ever filmed but it strikes me as brilliant, anticipating films like The Dirty Dozen (1967) and even Hitchcock's own later Cary Grant vehicle, To Catch a Thief (1955), in which jewel-thief John Robie redeems himself by returning to the 'scene of the crime'. The present ending of Suspicion is of course a compromise, if only for the reason I've already given: it goes against the film's grain, in which Johnnie's amoral nature is continually being revealed to have further aspects, just as Will itself is boundless, with both good and bad sides forever revealing themselves anew. The present ending feels artificial, added just to end the film - and yet it has an ambiguity about it for those with eyes to see. (Ditto, for the ending of The Lodger.) Interestingly, Lesley Coffin sees this, and thinks that modern audiences also see it. She writes: 'modern-day audiences are more willing to accept that the film simply has an ambiguous ending rather than a happy one; while Fontaine may accept and be complicit with his behaviour, Johnnie will always be a manipulative and possibly dangerous man.' (p. 32) 'Possibly dangerous' is right. With the present ending, which feels so perfunctory - surely deliberately so, drawing attention to itself, like the 'fairy tale' happy ending of The Lodger - we are perfectly at liberty - indeed invited - to feel that Johnnie may be a sociopath who has already murdered his dear friend 'Beaky' Thwaite (Nigel Bruce) and may have similar designs on his beloved Lina. As Hitchcock was fond of saying, '"Each man kills the thing he loves" ... I think that's quite a common phenomenon, really.' Remember that we are talking about a 'surreal' film - like so many Hitchcocks - yet where the circumstantial evidence suggesting that Johnnie is a murderer is carefully established. The film itself points out that there was a real-life precedent for murder employing a brandy-drinking challenge (such a murder was committed by Englishman William Palmer, though the film mysteriously refers to him as 'Richard Palmer'), and it has carefully given Beaky some telling lines early on. For example: 'That Johnnie, he'll be the death of me.' And: 'He doesn't need more than one second to invent the most howling lie you ever heard.' (The frame-capture below shows Beaky with Lina waiting for Johnnie to 'explain' where the heirloom chairs have gone.) Just remember that latter remark when at the end Johnnie's arm ambiguously circles Lina's shoulder and he turns the car around for the couple to return home. Did he really mean that he only ever meant to kill himself? To be continued.

December 13 - 2014

[Taking a week off to meet deadlines, sorry. Back next time. K.M.]

December 6 - 2014

In coming weeks - with maybe a short break for Christmas later this month - I may be writing here some thoughts on Hitchcock's Suspicion (1941). This site already features an important page on Suspicion, written by Bill Krohn, which supplements other important material that is available, including essays by Mark Crispin Miller, Rick Worland, and Patrick Faubert and a further piece by Bill himself that appeared in the 'Hitchcock Annual' (2002 edition). And when this site is finally re-vamped in a couple of months, we will be featuring a piece on that film by Michael Walker (author of 'Hitchcock's Motifs'), published for the first time. My own work on Suspicion has been extensive - including an article that appeared in the hardcopy 'MacGuffin' (#7) - and Walker has given me permission to cite some it in the editorial remarks I'll be adding at the front of his piece. (Meanwhile, do look at Bill Krohn's piece here.) I just felt the need to brush up on the film again, you understand! From discussing it with Bill, and others, I remember it as hugely under-rated. Bill feels it to be a masterpiece, and I agree with him. As with several other Hitchcocks, once you grasp the principle on which it is constructed, it appears so ... elegant. No other word for it. Today I ran the first half-hour again, and the way in which the film carries you along - playboy Johnnie (Cary Grant) is audacious from the opening scene on a train, spinster Lina (Joan Fontaine) so susceptible to every whim and fancy as she quickly falls for him, though we can see he's probably a cad - is totally deft, and you have to cheer the script by Samson Raphaelson and such things as the film's score, by Franz Waxman, which is constantly (in a Hitchcock phrase) 'taking the curse off' one preposterous situation after another. Then, of course, there's the acting - although it can hardly be separated from Hitchcock's direction. For example, take the comedy of the moment when Johnnie, on returning from their honeymoon, tells a shocked Lina that he is broke (implying that they may have to live on money from her wealthy parents). Quickly recovering, she tells him that there's another possibility to consider - for him to get work. Close-up of Johnnie, obviously taken aback: 'Work?' (Here, a musical 'stinger' underlines his shock.) Close-up of Lina, shrugging, as if to imply the lack of alternatives: 'Yes, work.' Close-up of Johnnie (who mid-way through his remark airily waves a pair of sugar tongs): 'What, you mean put on old clothes and go out with a shovel?' (See frame-capture below.) That moment with the sugar tongs is both expressive and proleptic. It is the first moment when Johnnie will hold up a white object, brilliantly illuminated - a later such moment, of course, occurs at the film's climax where Johnnie carries upstairs to Lina a glass of milk that may be poisoned (and inside which Hitchcock had secretly put a light, to make sure we didn't look away.). I'm not suggesting that Hitchcock put a spotlight (say) on that piece of sugar that Johnnie flourishes so distractedly, but I am noting that the gesture was obviously scripted and that the sugar was certainly meant to be seen by us! It would be just like Hitchcock to have thought of that moment as both a comic underlining (of Johnnie's double-take of a moment earlier) and as foreshadowing a much more important parallel moment later: part of his conditioning of audiences via 'style'. Roughly comparable in Suspicion is its 'postal' motif, as Bill Krohn and I call it. In the film's opening scene on the train, Johnnie is caught out by a uniformed ticket-inspector for travelling in a first-class compartment on a third-class ticket; when the official demands payment of the balance, Johnnie prevails on Lina, sitting opposite (and whom he has just encountered), to help out with a penny-halfpenny stamp. Handing it to the official, he says, 'Legal tender, old boy', and adds: 'Write to your mother!' Fairly evidently, the moment is our best evidence in support of what Hitchcock told Truffaut, that he had intended to end the film with a scene in which Johnnie unwittingly incriminates himself by mailing at Lina's request, just before she (masochistically) drinks the poisoned milk, a letter to her mother - in which she explains why she is content to die but cannot allow Johnnie to roam free. Presumably, Johnnie would have put the postage on the letter before mailing it, thus bringing the film full-circle and repaying his penny-halfpenny debt to Lina. (He would have exited, whistling.) To be continued.

November 29 - 2014

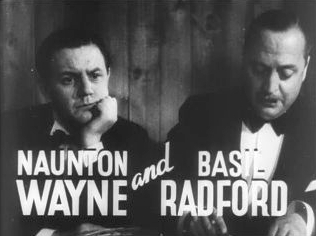

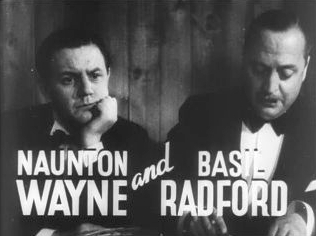

About five minutes into The Lady Vanishes (1938), Hitchcock gives us the conversation in a European inn between Charters (Basil Radford) and Caldicott (Naunton Wayne) in which they speculate on whether they'll get home 'in time'. Charters is doubtful: 'That last report was pretty grim ... England on the brink ... looks pretty black.' (Frame-capture below.) Hitchcock is happy to let the audience think that the two Englishmen are speculating about whether they might become marooned in a foreign country when war breaks out - thus setting the underlying sense of peril on which the rest of the film will trade, both for suspense and for several of its gags, invoking English parochialism in the face of other people's adversity. Typically of 1930s English Hitchcock, the basic idea was not original. (Hitchcock's 'Cromwell Road brains trust' would take on board ideas from anywhere, frequently without acknowledgement. For example, the handcuffed couple at the centre of The 39 Steps come from a 1927 novel, 'Mr Priestley's Problem', by A.B. Cox.) In this case, the idea came from a popular novel by A.G. Macdonell, 'England, Their England' (1933), a satire on Englishness as seen through the eyes of a young Scot, Donald Cameron. Its account of a village cricket match was often anthologised separately as a masterpiece of comic writing. But what Hitchcock and his team seized on was a witty passage where Donald, walking through London, is alarmed by seeing newsvendors' placards saying 'ENGLAND OVERWHELMED WITH DISASTER' (the 'Evening News') and 'IS ENGLAND DOOMED?' (the 'Star'). The subject, he discovers, is the impending defeat of England in a cricket match against Australia! To Hitchcock's credit, the basic idea of Charters and Caldicott's obsession with cricket is beautifully integrated into the larger story and themes of The Lady Vanishes. And they, together with Iris (Margaret Lockwood) and Gilbert (Michael Redgrave) eventually lead the way in rallying the English train passengers in a showdown with the villains who have kidnapped English governess Miss Froy (Dame May Whitty) because she knows too much. One of Hitchcock's perennial themes is bringing people - ultimately the film audience - out of themselves, and that's the case here. What is interesting is how, meanwhile, just about everyone in the film seems lost in a private (subjective) world, and that includes its heroine Iris. An early encounter with Charters and Caldicott seems to quickly reach an impasse. Iris: 'I don't see how a little thing like cricket can make you forget seeing people.' Her phrasing is echoed later in the film by Caldicott himself. The kidnapped Miss Froy has been rescued, and she says something that should be fairly evident: 'We're not in England now.' But Caldicott (for the present) can only respond: 'I don't see what difference that makes.' Moments later, he is puzzled again when Gilbert grabs a chair and knocks out a soldier (who boasts he went to Oxford) sent by the villains to negotiate. Gilbert explains off-handedly: 'I was at Cambridge.' Charters: 'Well, what's that got to do with it?' Even the chief villain, the urbane brain surgeon Dr Hartz (Paul Lukas) has his blind spot. The false nun who had been minding the bandaged-up Miss Froy suddenly rounds on the doctor and in broad Cockney chides him: 'You never said the old girl was English.' Dr Hartz: 'What difference does that make?' Notice that Hitchcock maintains a joking tone wherever possible because that very tone implies the film's message, that we're all basically the same, if only we could see it. Sport is used as a convenient metaphor wherever possible, and it's significant that Hartz, finally defeated, uses an English idiom to congratulate his opponents: 'Jolly good luck to them.' (Twenty-one years later, the 'realpolitik' of North by Northwest has its defeated villain, played by James Mason, take a slightly different tone: 'That wasn't very sporting of you, using real bullets.') So the audience of The Lady Vanishes was allowed to treat the events as finally all a joke - if they wanted to. It was no doubt the safest way of appealing to the widest possible audience at the time. Otherwise, the sort of complacency on view in The Lady Vanishes looks forward to later Hitchcock films such as The Birds. (The jaded rich-girl character of Iris foreshadows that of Melanie in the 1963 film.)

November 22 - 2014

Still on Jamaica Inn ... but, first, I looked again at the night-sequence mentioned last time from The Paradine Case and see that my memory had simplified it. It does indeed imply a shared bond, with its successive shots of the principal characters dining at home or lying in bed (nobody speaks) after the opening day of the trial. What I had forgotten was how the sequence opens and closes with low-angle shots of the war ruins adjoining the Old Bailey. The implied 'common cause' (against a recently defeated enemy, and now the task of rebuilding) symbolises the bond I mentioned, a bit like how the incursion by foreign fishing trawlers sets in motion The Manxman (1928) and unites the otherwise divided characters. But of course The Paradine Case was based on the 1933 novel by Robert Hichens, an avowed Schopenhauerian, so it's legitimate to further infer that the bond is one of shared cosmic 'Will', so demonstrably operating in many Hitchcock films (such as The Birds). Jamaica Inn (whose credits sequence influenced that of The Birds) is such a film. The sad thing is that none of its characters can rise above their individual histories to embrace the bigger picture: Squire Pengallan tries, but only succeeds in becoming a master villain, increasingly evil. Also, consider the character of Jem Trehearne (Robert Newton). His affection for Mary Yellan (Maureen O'Hara) will allow a conventional happy ending, but the film doesn't stress it. In fact, Jem - a disguised law officer and naval lieutenant - is made to look a bit of a simpleton at times. After he and Mary escape Joss's cutthroats and arrive at the Squire's mansion - not knowing that they have come to the home of the wreckers' ringleader - Jem prances almost boyishly around the mansion in rags and bare feet. Eventually given a set of clothes belonging to the Squire's guest, Lord George (Basil Radford), he acts even more cocky, like a fop: see frame-capture below. The Squire of course leads him on. The pay-off will come later when the Squire tells the tied-up Jem the facts and that there will be no rescue by 'Captain Boyle' from Truro: 'There is no Captain Boyle, consequently there will be no military.' This is the nadir in Jem's fortunes and those of Mary and her relative, Aunt Patience (Marie Ney). Even Jem's relationship with Mary had plunged into despondency after she had found out that he was working for the law against her aunt and uncle. For a time, she acts the aggrieved young woman who resents having fallen for a man who has manipulated her: shades of Pamela (Madeleine Carroll) and Hannay (Robert Donat) in The 39 Steps. However, as in that film, Hitchcock is also allowing Mary to signal her pluck and courage, as she will notably do when she escapes from Joss's men and improvises a beacon to save an apparently doomed ship - and again at the climax when she escapes the Squire's clutches. (The actress's qualities are on display in her first feature film, My Irish Molly (1938), which I watched recently: I understand that Laughton had spotted her and arranged for her to make the film, which he was then able to show to Hitchcock.) The wrecking scenes themselves are a mixture of ingenious sets and rapid cutting of details (e.g., sailors jumping from mastheads) and some less-than-convincing group-shots and model-shots. (The scenes do make effective use of realistic-looking waves and cascading spray, a foretaste of the storm-at-sea in 1944's Lifeboat.) Inevitably one comes back to Hitchcock's statement that he was mainly interested 'in the Jekyll-Hyde mentality of the Squire'. Right at the end, the by-now crazed Pengallan tells Mary: 'Any man of sensibility would rather see you dead first [than raising children with a non-aristocrat like Jem].' The logic is practically identical to that of the toffish Ivor Novello character in The Lodger (1926) who - the film strongly hints - killed his blonde sister at her coming-out ball to save her from being sullied by the world. (A fantasy of 'eternal childhood', of children who never grow up, was almost commonplace in Victorian and Edwardian drama and fiction, as brilliantly analysed by Jackie Wullschläger in 'Inventing Wonderland' (1995).) In turn, you can see variants on this mentality working in Rebecca (1940) - where Maxim (Laurence Olivier) tells 'I' (Joan Fontaine) never to 'be 36 years old' - and in Psycho, where 'Mother' intervenes to prevent her son (Tony Perkins) from taking a rival lover. 'A boy's best friend is his mother', as Norman himself says. QED.

November 15 - 2014

Jamaica Inn occurs after the death of the 'mad king' George III and the accession of his son George IV. The year is 1820. When we first come upon Squire Pengallan (Charles Laughton), he is toasting the new monarch - in whose circle he had mixed for a while. But he now professes contempt for the new king. 'The fat fool ... [nowadays] he's nothing but a painted bag of matasquita and plum pudding!' (Have I quoted that correctly? Anyone? Also, see frame-capture below.) On the principle of looking after Number One, the Squire seeks to insulate himself from anything that would drag him down - presumably including madness. But the effort is palpably a taxing one, given the isolation in which the Squire increasingly finds himself. (In Psycho, of course, Norman Bates reports that 'they moved away the highway' ...) Invisibly he surrenders some of his powers, and the signs of denial of reality slowly increase. He uses his manservant Chadwick as some people today use the Internet - as a substitute for one's own memory. Asked which lake he had most admired last summer on his annual excursion, the Squire relays the question to Chadwick and is told, 'Lake Windermere, sir!' Such 'schizophrenia' is partly what Jamaica Inn is about. As noted, the lives of the slaughtered sailors murdered by the gang of wreckers, led by Joss Merlyn (Leslie Banks), matter nothing to the Squire, consciously. There is, however, a startling passage in Chapter 8 of the novel in which Joss, drunk, vividly recalls to Mary exactly how he had killed even women and children, smashing in their faces with rocks, then leaving them to drown. '[Mary] felt deadly sick ... She looked up at her uncle, and she saw he had sloped forward in his chair ... and his hands were clasped as if in prayer.' It's a study in damnation, all right (of the wreckers and, by extension, the Squire), yet Hitchcock knew that nothing is simple. We had some discussion, apropos Jamaica Inn, on our discussion group this week, of how notions of 'good faith' and 'bad faith' occur in Hitchcock films. I posted as follows: 'Both the Squire and Norman Bates seem finally to enter a state where their inability to face reality tilts them into psychosis, a form of bad faith. (Also, the screenplay of Rope, filmed in 1948, indicates that Brandon is essentially mad from the time he loads a pistol to await the returning Rupert.) The Squire conveniently becomes a Byronic hero; Norman conveniently becomes his own mother ...' Jamaica Inn is clearly about degrees of bad faith (starting with that 'old Cornish prayer' but also such things as Patience's refusal to let herself know where an anticipated wreck will occur - as if that made her less culpable), and likewise Psycho goes out of its way (as Raymond Bellour noted long ago) to show degrees of dishonesty/madness in society. So when a student [of correspondent MP] says of Norman Bates (or a character says of Squire Pengallan), 'he can't help himself', Hitchcock is showing that it's not really that simple: why did the character pass up the chance to settle with God or his conscience before conveniently becoming mad? But that question, in turn, isn't simple either! (Graham Greene explores questions of 'free will' in a novel like 'Brighton Rock' - as does Hitchcock here and in Psycho.) And then there's the aspect I mentioned in passing last time: how (to paraphrase Georges Bernanos) if we really knew 'how closely we are bound to each other in good and evil, we truly could not live'. Again I say: such 'schizophrenia' is what Jamaica Inn is about. It's a theme also adumbrated, very beautifully, in The Paradine Case (1947) which includes a cross-cut sequence, on the evening after the first day of the trial, in which we see the various characters asleep or lying in bed, and a linking high-shot of the city itself that implies, like so many Hitchcock films, that 'we are all responsible'. (I have analysed this sequence previously. Maybe I'll come back to it next time.) Also, I mentioned last time The Trouble With Harry (1955) and its benign allegory of a New England community where, indeed, everyone is 'bound to each other in good and evil' - but happily, having been granted an epiphany of what it would feel like to live free of the guilt that only a joyless puritan like Calvin Wiggs (Royal Dano) insists on! Far from being escapism, The Trouble With Harry is about what Hitchcock suggested, 'the commonplace raised to a higher level'. To be continued.

November 8 - 2014

Daphne du Maurier liked to 'borrow' basic plot ideas from other authors' successes, and in the case of 'Jamaica Inn' (1936) she loosely based her villain - a clergyman, Mr Davey, who is secretly a pagan-worshipper and leads a band of wreckers in 19th-century Cornwall - on the character of Doctor Syn in the series of novels by Russell Thorndike (1885-1972). (Michael Balcon produced, and Roy William Neill directed, a film of Doctor Syn in 1937, starring George Arliss.) To an extent, the Reverend Davey is a forerunner of the fair-seeming Rebecca in du Maurier's novel of that name (1938): both feel out of place in their own time. As Davey says: 'I do not belong here, and I was born with a grudge against mankind. Peace is very hard to find in the nineteenth century. The silence is gone, even on the hills. I thought to find it in the Christian Church, but the dogma sickened me ...' (Chapter 17) True, 'Rebecca' was always the superior novel - not least because of the title-character's almost Nietzschean (but chilly) polymorphous perfection - but in both cases a part of the author sides with the character and thereby sharpens the critique of a particular Cornish community that has become corrupt or too-rigid. (Simultaneously, du Maurier's heart is in the timeless Cornish landscape - which makes for gripping reading by her many fans.) In the event, of course, the villain of Jamaica Inn had to be changed for the film version: somebody realised that a pagan-worshipping clergyman would not be acceptable in the US market. So now the leader of the wreckers has become Squire Pengallan (Charles Laughton), a distant descendant of Doctor Caligari in the German film classic of that name (produced by Erich Pommer, the producer of Jamaica Inn): both are authority- figures seemingly above suspicion. (From another perspective: the plot-device of a 'benign' official who proves evil soon became hoary, used by everyone from Agatha Christie to Hitchcock again in 1945's Spellbound, based on the 1928 novel, 'The House of Dr Edwardes'. A variant would be Psycho.) The script of Jamaica Inn is ingenious in how it adapts the Reverend Davey's attributes to Squire Pengallan. Davey's death, after taking Mary Yellan captive, and both of them pursued across the moors by Jem (who in the novel is Joss Merlyn's brother), occurs when he is shot in the shoulder and plummets off a crag: compare Pengallan's death in the film after leaping from a ship's rigging. Even Davey's pagan qualities are, in a sense, transferred to Pengallan, both in the latter's corrupting taste for figurines and precious objects (for which he is prepared to sacrifice lives) and his association with the community of 'lost souls' who congregate at Jamaica Inn and display various superstitions. (One of the gang, his hand-mirror shattered, attributes his arrest straight afterwards to the incident. A variant on such belief in superstition occurs in Hitchcock's benign 1955 The Trouble With Harry, where Captain Wiles (Edmund Gwenn) consistently notes Nature's 'omens' - and patently ignores the call to church made by the ringing bell at the film's start. Mind you, the film allows that its essentially decent characters have their lives to live and, in doing so, manage to display what Captain Wiles calls 'hasty reverence' - a form of sacrament in itself.) One of the Jamaica Inn gang is Harry the Pedlar (Emlyn Williams) who is forever whistling (shades of The 39 Steps). At times this seems callous, as when he prepares to string up Jem (Robert Newton) - but he maintains it to the very end, when his own execution is imminent. So Jamaica Inn is a study in damnation - and in ways of living and dying. Also, as noted last time, something like Georges Bernanos's observation applies: 'I believe if God gave us a clear idea of how closely we are bound to each other in good and evil, we truly could not live.' Such insights inform many of Hitchcock's films (1947's The Paradine Case, say), but are too seldom noted. More on this next time. Meanwhile, I thank correspondents MP and DF who both nailed what the coach driver says at the start of the film (see last week, and frame-capture below): 'Queer things [go on at Jamaica Inn]. I won't stop there, not if you were to offer me double fare.' (So Mary Yellan gets carried past her intended destination - and delivered straight into the clutches of the increasingly mad Squire.) (On another matter, we congratulate actor/producer Norman Lloyd on achieving his 100th birthday this week.)

November 1 - 2014

Jamaica Inn (1939) isn't the unmitigated failure you sometimes hear it called, and in light of its pending restoration (see News below), I took another look at it this week. Hitchcock said that he was mainly interested 'in the Jekyll-Hyde mentality of the Squire', and in several ways the film is a precursor of Psycho. Both are studies in solitariness - always a Hitchcock motif - and of damnation. Squire Pengallan (Charles Laughton) is trapped by his very refinement and belief in his own Byronic rightness: at one point you hear him refer to a time when he successfully gambled large sums to return his estate to the black. But then, with options running out, and his self-image (as a wealthy man of the gentry) everything, he aligns himself with a band of local cut-throats and wreckers: as so often in Hitchcock, a descent into irreversible corruption is signalled. In later films, such as Psycho and Marnie, Hitchcock would actually insert a literary text to point the lesson that is being ignored: surrender to God's greater plan. There is just a hint of that here: the hypocritical 'old Cornish prayer' that sets the (false) tone at the very start. On the other hand, as I note in 'The Alfred Hitchcock Story', a motif of determinism is allowed to run through the film. 'People can't help what they are', Aunt Patience (Marie Ney) says of her wrecker-husband Joss (Leslie Banks) and herself. 'He can't help himself', Mary Yellan (Maureen O'Hara) says of the Squire at the climax. (Some people always want to think the best of others, and to find excuses for them, and Hitchcock - a good Catholic - wasn't going to actually forbid such generosity in his audiences. Interestingly, I'm told by correspondent MP that a film class he conducts was recently shown Psycho and then asked who was the most 'sympathetic' character. The 'winner' by a long way was Norman Bates: 'he can't help himself', as one girl literally put it. And when you think about it, what Hitchcock called 'that fine line' between two opposed states is very hard to pin down. 'I like films with plenty of psychology' he once said, bringing us back to why he filmed Jamaica Inn at all.) There's a scene mid-way through the film (intercut with the actions of the wreckers at nearby Jamaica Inn, thereby adding an extra dimension) showing the high-handed way in which the Squire treats his tenants. To a surly-looking 'rank radical' he gives short measure: 'You're not as good as me, your birth was against it from the start and circumstances since then have only made matters worse.' (But could the Squire be unknowingly describing his own decline, where deterministic 'circumstances' have started working against him too?) On the other hand, when one tenant comes up short with his dues, and gives the excuse that his son can't work because of an injured leg that won't heal, Pengallan refers the lad straight to the local doctor 'with my compliments'. And when his eldest tenant, an old lady, mentions a leaking roof, Pengallan is generosity itself, arranging for her to be given a new roof. Yet this is the man who knowingly has allowed a hundred sailors to go their deaths at the hands of Joss and his wreckers. I love the last shot of the film (frame-capture below) in which the ever-loyal retainer Chadwick (Horace Hodges) is left saddened and depleted by his master's death, whose resounding cry of 'Chaaadwick!' still echoes. (Hitchcock probably took this trope from John Ford's 1937 adaptation of Kipling's Wee Willie Winkie.) The image, while ambiguous (it shows a man pitifully responsible for his own sado-masochistic entrapment - but what else was he to do, become a 'rank radical'?), sums up the mystery that lies at the heart of the film: that interaction in which we all share. To quote another Catholic author, Georges Bernanos: 'I believe if God gave us a clear idea of how closely we are bound to each other in good and evil, we truly could not live.' I think of what Hitchcock said after completing Psycho: 'Reality is something that none of us can stand, at any time.' And indeed, that final image of Chadwick seems to me almost as poignant as our last view of a depleted Norman Bates, at the end of Psycho. Now, I'll have more to say about Jamaica Inn next time. But meanwhile I'm wondering if anyone can discern what is said by the stagecoach driver near the film's start. Whatever else, it isn't what is reported by Harry and Michael Medved in their rather silly book, 'The Fifty Worst Movies of All Time' (1978). According to them, the driver says: 'Queer things [go on at Jamaica Inn]. I once slept there and not a sheet was on my double bed.' (p. 120). What wild imagination! My ears tell me that the driver says something more like, 'Queer things. I once stopped there and [was charged] double fare.' Anyone?

October 25 - 2014

[No entry this week - instead we have added some News & Comment items. KM]

October 18 - 2014

Dear reader. Just in case you didn't know, there's a feast of recent books on Hitchcock out there, of varying quality. Essential reading must be William Rothman's 'Must We Kill the Thing We Love? Emersonian Perfectionism and the Films of Alfred Hitchcock' (2014). It complements the added chapter, on Marnie, in the Second Edition of Rothman's 'Hitchcock: The Murderous Gaze' (2012). The latter includes this: 'The Emersonian point of Mark's fable [of the flatid bugs that 'live and die in the shape of a flower'] is that everything in nature is beautiful, because everything in nature strives instinctively to live, to exist, to become its singular self - including Marnie.' (p. 408) Rothman specifically applies this to 'those whose instinct is to protect themselves from predators by appearing other than what they are' (pp. 407-08) while seeing that 'without taking steps toward realizing our world, toward making our society a more perfect union, it is not possible to [even start to go] in the direction of the unattained yet unattainable self' (pp. 423-24). Hmm. I believe that Hitchcock may indeed have had the Catholic notion of the Communion of Saints in mind when making many of his films. At any rate, now compare Rothman's further observation concluding his 2014 book: 'Hitchcock is a moral artist. At the core of his moral vision is the sad truth that to keep faith with the better angels of our nature, we have to be willing to kill. But we also have to be willing to love. Is this a happier truth? Not if it is also a truth [as Hitchcock said he believed] that "each man kills the thing he loves." ... But Mark Rutland is Hitchcock's ultimate counterexample - an exception that disproves the rule. At the conclusion of Marnie, the film's protagonist, thanks to Mark's help, is changed. Trapped since childhood by her fear that she was fated always to kill the thing she loves, Marnie has finally freed herself from her "private trap," her compulsive need to "clutch at things." She has not escaped from her mortal life, her humanness.' (p. 254) Marnie is also the topic of an appreciative new (2014) monograph in the BFI Film Classics series, by Murray Pomerance. The author has advanced from his position in 'An Eye for Hitchcock' (2004) where he almost seemed to damn Hitchcock's late masterpiece with the faint praise of 'This ... melodramatic tale ... in which we take pleasure in some of the very deftest writing and most carefully modulated acting in all of Hitchcock' (p. 131). (He was, of course, simultaneously mocking the film's detractors who dismissed the film as nothing but melodrama.) Then, in 'Alfred Hitchcock's America' (2013), Pomerance concentrated on the rich sociological content, and poetry, of the American Hitchcocks. For example, he dwelt on the stop-off in Marnie at a Howard Johnson's diner. Excerpt: 'The waitress has swung back like a pendulum, this time with the bill and a little regulation salutation, "You folks be sure and come back, now." In road culture, this mantra is always translated as a general, not a personal, invocation, as in, "Come back to the company, not necessarily this branch. The company wants your affiliation wherever you go, and wherever you go Howard Johnson's will be there to serve you at the side of the road."' (p. 191) (This whole road sequence has some of the grey impersonality that Hitchcock also invested in the office scenes at Rutland's and the racetrack scene, signalling Marnie's loveless state. All superbly, beautifully done.) The back cover blurb of the new monograph includes this: 'Murray Pomerance here [weaves] critical discussion together with production history to reveal Marnie as a woman in flight from her self, her past, her love, and the eyes of surveilling others.' Of the bloody climax - specifically the shot of the dead sailor's blood-coated shirtfront (frame-capture below) - Pomerance evokes it thus: 'That bloody screen. It constitutes the human - the living - condition; we all experience everything through blood. Blood is biology, revivification, identity. It is always somehow blood that speaks, not the calculating mind. Shakespeare knew this, and Hitchcock after him.' pp. 80-81) (Rothman would no doubt invoke Emerson to make a similar point. Catholics might invoke the Mass, and specifically the Eucharist. I see an analogy with Schopenhauer's concept of the world's Will - the life/death force - and how, for example, great drama offers the opportunity to perceive and come to terms with it. Marnie is that great.) Finally, some other books. Neil Badmington's 4-volume anthology, 'Alfred Hitchcock' (2014), sells for (US) $2,741.45. I haven't yet seen - let alone bought - it. On the other hand, I have in front of me, but still unread, both Katalin Makkai's edited volume for Routledge's Philosophers on Film series, 'Vertigo' (2013), and Jonathan Goldberg's monograph for a Canadian publisher's Queer Film Classics series, 'Strangers on a Train' (2012). (Readers are welcome to send me reports on such publications as these.)

October 11 - 2014

As noted last time, Ivor Novello in The Lodger (1926) appears as something of a Christ-figure from the moment he goes to the window on hearing a news-vendor calling out about the latest 'Avenger' killing, and a crucifix-like shadow is cast on his face (see frame-capture below). Given that the story concerns how the character has a pronounced affection for his late sister (did he, though, kill her, not wanting anyone to take her innocence?), related to his no-less strong attachment to his late mother (prefiguring Norman Bates in Psycho), it seems to me legitimate to think that the filmmakers may have been influenced by Ernest Renan's popular 'Life of Jesus' (1863) which was featured in a psychological study by Albert Mordell, 'The Erotic Motive in Literature', first published in 1919. In a chapter called "The Oedipus Complex and the Brother and Sister Complex", Mordell suggests that Renan's extreme attachment to his sister explains 'the gentleness, the moral tone, the kindliness we find in his writings', and adds that Renan's 'love for his sister was a great factor in his making his Jesus somewhat effeminate'. (Just before the scene at the window, the Novello character has recoiled from a series of pictures of young women, culminating - surely significantly - in Millais's "The Knight Errant", 1870, which shows a knight in armour rescuing a nude damsel tied to a tree, her oppressors fleeing in the top right-hand corner of the image: The Knight Errant.) Also, not incidentally, the Oedipal situation is effectively defined by The Lodger as being 'weak' (again as in Psycho): that is, the Novello character's own father is never seen, while the father in the Bunting household is a mildly comic figure (like Mr Newton in Shadow of a Doubt). In short, the young Hitchcock and his team appear to have done ample research - at a time when Freud was becoming more widely known and his influence was reaching the stage and screen in France, England, and Germany - and they appear to have pulled out all the stops to portray Novello's character as a psychological 'case'. In other words, they had made an astute assessment of the Novello persona - which we've been analysing here in recent weeks - and decided to do with it something 'different'. The Lodger was eventually a big box-office success so that, perhaps not surprisingly, Novello agreed to also star in Hitchcock's next film, Downhill (1927), based on a stage play by Novello himself and his actress friend Constance Collier. Ivor Montagu initially worked on the screenplay and was going to edit the film, but apparently he fell out with Hitchcock. In any event, not wanting to portray Roddy as too effeminate - perhaps the filmmakers felt they had gone too far last time - he reported: 'I have worked in two strong feminine parts ... I have also endeavoured to preserve the hero's character. If he is to marry a clean girl, we must keep him as clean as possible. He can be foolish, and quixotic, but not unmanly.' (Quoted by Williams, p. 39) Montagu's name isn't in the Downhill credits. According to Geoffrey Macnab, Montagu evidently did not understand the nature of Novello's appeal, for it was precisely his 'androgynous quality ... which made him a star in the first place. Like Valentino in Hollywood, he contradicted received ideas about masculinity' (Macnab quoted by Williams, p. 40). Maybe, but our analysis has also been about how cleverly Novello adapted his stage and screen appearances to always maintain a playful ambiguity. For a final insight into Novello, I turn again to James Harding's biography. Max Beerbohm (1872-1956), the writer and caricaturist (Hitchcock owned many of his works), had written a short story "The Happy Hypocrite" (1897) to illustrate his theory that we should all adopt a mask in order to live up to our better natures. (The story reads a little like a variant on Oscar Wilde's 'The Picture of Dorian Gray'.) Via a one-act stage version, it eventually became a three-act play written by Hitchcock's friend, the lesbian author and playwright 'Clemence Dane' (Winifred Ashton), for Ivor Novello to star in, in 1936. (By the way, Dane was apparently adept at peppering her conversations with supposedly innocent double-meanings. While dining with the Governor of Jamaica and his lady, she remarked of a mutual acquaintance: 'Do you remember the night we all had Dick on toast?' Hitchcock would have loved such occasions, and had some similar bon-mots of his own!) Significantly, Harding reports that the play held special appeal for Novello, not least because its mask theory 'coincided with his own experience'. It also gave him a meaty role that proved to doubters that he really could act. (Harding, pp. 126-28)

October 4 - 2014

[Revised] Michael Williams ('Ivor Novello: Screen Idol', BFI, 2003) spends a lot of time analysing the moment in The Lodger (Hitchcock, 1926) when the Novello character first arrives at the Buntings' front door, seeking a room to rent, and startles Mrs Bunting (Marie Ault) by his unusual appearance, including his face whose lower features are concealed by a muffler. (See frame-capture below.) Of course, contemporary audiences immediately spotted that the face was that of their adored Ivor - who had first shot to fame when just out of his teens by composing the song "Keep the Home Fires Burning" which became almost a second wartime National Anthem. Impossible to think badly of such a hero! (Teasingly, then, after Novello started making films soon after the War, many of their plots had him committing sexual misdemeanours: adultery, making advances to his best friend's wife, impotence. In The White Rose, 1923, he even played a priest who gets Mae Marsh pregnant.) And now here was Hitchcock teasing his audience that the Novello character might be 'The Avenger', based on Jack the Ripper! If Mrs Bunting is startled, she has reason to be, given the film's opening scenes showing a panicked London. But Williams has a theory of his own: the youthful figure behind the muffler has reminded Mrs Bunting - and contemporary mothers watching the film - of all the young men who went to war and didn't return. Ivor is their representative, and his appearance at the Buntings' door, materialising out of the 'London fog' (as the film's subtitle has it), is almost ghostly. And when we quickly realise that this 'horror-haunted man' (that's Williams's phrase) might represent 'the terrors of modern warfare', any suspicions of the Lodger's malignity are in conflict with our (or Mrs Bunting's) other feelings. (Arguably there's some support for this theory in Hitchcock's Spellbound, 1945, where Gregory Peck plays another troubled young man, an amnesiac, whose symptoms may have multiple causes, including a form of shell-shock or PTSD as we might diagnose it today.) On the other hand, Richard Allen finds a quite different connotation in Novello's appearance at the Buntings' door: our first full-length glimpse of the character shows him to be 'slim, ethereal and phallicly rigid' (Allen, quoted by Williams), allegedly evoking the vampire Count Orlok in F.W. Murnau's Nosferatu (1922) who welcomes an unsuspecting young man to his Transylvanian castle. And, yes, I wouldn't put it past Hitchcock and his team (including screenwriter Eliot Stannard, editor and friend Ivor Montagu, assistant director and wife Alma Reville) to have intended such a link. You think of Hitchcock's American 're-make' of The Lodger, i.e., Shadow of a Doubt (1943), and how the house-guest there, Uncle Charlie, another caped figure, turns out to be the Merry Widow Murderer! Still, there's another possibility. For what it's worth, my own theory is that the makers of The Lodger were thinking of the murderous young somnambulist Cesare in The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (Robert Weine, 1920). He, too, is seen to be 'slim, ethereal and phallicly rigid' when Caligari first displays him to a fairground audience (and the film audience) by swinging open the lid of an upright, coffin-like box. The very title-designs of The Lodger, by artist Edward McKnight Kauffer, seem part-derived from the stylised German Expressionist designs of Caligari; moreover, there is even a moment in the titles of The Lodger when the image resembles a coffin opening and closing on its titular figure. And another thing. Cesare, of course, had been played by handsome young Conrad Veidt, who was like the German equivalent of Novello - even to the fact of their both being the same age and both gay. (Even more than Novello, Veidt did not attempt unduly to conceal his gayness, appearing in the 1919 'gay lib' film, Anders als die Anderen/Different From the Others.) To clinch my case, there is the fact that Alma Reville scripted the 1935 film The Passing of the Third Floor Back (d. Berthold Viertel) which shows a caped figure arriving at a London guest house, seeking a room - a scene obviously based on the one in The Lodger. And who plays the 'Christ-figure' whose presence in the guest house will henceforth transform the lives of the other residents? None other than Conrad Veidt! Moreover, recall that Novello in Hitchcock's film is also presented as a sort of Christ-figure. To be concluded.

September 27 - 2014

[Revised] Again this time, I can't possibly summarise every part of Michael Williams's elaborate argument about just what Ivor Novello was up to in his various film performances. The essence, of course, is that they were knowingly designed to camouflage his (Novello's) gayness. Another way of putting the idea is that audiences were encouraged to appreciate the star's handsome, supposedly virile 'essence' while being also treated to his range and depth of feelings, something rare in leading men. That Hitchcock in The Lodger wasn't prepared to be so deceiving - at least, not in the by-now clichéd way - but preferred to keep everything enigmatic from the moment of Novello's first appearance, the character's face half-concealed by a scarf, indicates a new 'holistic' approach to film style. In Hitchcock's films thereafter, including Downhill that immediately followed - again with Novello - both 'appearance' and 'reality' are themselves called in question, effectively constituting a worldview. Such 'dignity of significance' is missing from many other, more opportunistic narratives - such as that of Novello's 1926 film The Triumph of the Rat, released at the same time as The Lodger, and which I watched this week. The Triumph of the Rat was a follow-up to The Rat (see last time), and was again directed by Hitchcock's recent mentor, Graham Cutts. I was reasonably entertained: Cutts's films are like variety shows, typically well-paced and with diverse elements, so that you're seldom bored. Nonetheless, I can agree with James Harding's estimation: 'Despite a lavish fancy dress ball intended to impress the audience, The Triumph of the Rat soon dwindles into bathos and incredibility.' ('Ivor Novello: A Biography', 1987, p. 60) It's only loosely a sequel to The Rat. Reformed gangster Pierre Boucheron (Novello) has now joined the ranks of Paris society, with which in the previous film he had briefly flirted in the person of Zélie de Chaumet (Isabel Jeans - playing the same character here). Once again, early scenes are designed to show how assured and dashing Novello is. In the frame-capture below, he kisses Zelie's hand while watched enviously by the film's 'silly old ass' type, the monocled René Duval (Charles Dormer), who laments not being successful with the ladies - despite his writing poetry with titles like 'Purple Passion'. On hearing this, Boucheron barely conceals laughter. When René asks him his secret, Boucheron answers, 'Don't you know, old chap, that in love there are no rules?' The rest of the film is about Boucheron's further sallies into love, including an enforced return to The White Coffin nightclub - suddenly he needs work - where the girls welcome him as before, but new apache rivals prove hostile. Not only are there no rules in love but there are no guarantees either. By the end of the film, a defeated Boucheron is back on the Montmartre streets while at The White Coffin the dancers move in a slow, sad rhythm. In other words, the second half of The Triumph of the Rat - ironic title - is about Boucheron's degradation, which seems to fit the pattern I noted last time, whereby a typical Novello film, having established his 'virility', allows him as wide as possible an emotional range, to further impress his legion of fans. (For example, a show of suppressed anger by Boucheron at one point is impressive.) Degradation will also be the main motif of Novello's second film for Hitchcock, Downhill (1927). But still, why did Novello allow himself to be cast in Hitchcock's The Lodger, which appears an aberration from the usual pattern? That's not an easy question to answer! If the lodger character isn't exactly effeminate, he is certainly neurasthenic, and Hitchcock seems to have enjoyed itemising the character's many mannerisms under stress. Following a hint from Williams, I suppose the fact that the character is a toff, a gentleman, has a lot to do with Novello's accepting the role. Once a gentleman, always a gentleman - and provided contemporary audiences felt that Novello stays gentleman-like to the end, when he appears both exonerated of murder and the heir to his family fortune - and the possessor of Daisy Bunting's hand in marriage - well, who could question his essential 'worth'?! The very knowledgeable Williams invokes Oscar Wilde, specifically 'Wilde's study of the Delsarte voice training system while in America in 1882, to which "gesture and pose" had been recently introduced, that enabled him to become fluent in the art of posing, and to "get away" with an actively constructed, socially visible, but carefully masked homosexual identity'. ('Ivor Novello: Screen Idol', 2003, p. 35) More next time.

September 20 - 2014

This week I finally caught up with the Ivor Novello film The Rat (1925), directed by Graham Cutts and produced by Michael Balcon for Gainsborough. A huge popular success, it illuminates Hitchcock's The Lodger (1926) in ways that I'll suggest. Note, though, that I'm indebted to Michael Williams's superb study 'Ivor Novello: Screen Idol' (BFI, 2003) for my main argument, which is that Novello's film performances were consistent-to-a-purpose, one which the actor knowingly adopted. Also, that certain comments by Hitchcock to Truffaut about The Lodger, suggesting that Novello's casting meant that the character's guilt or innocence could not be left ambiguous, are misleading. (In fact, that is something I have long maintained, most recently, in an enjoyable correspondence with SG.) About the last shot of The Lodger Williams asks rhetorically, 'Is this really a closure that obliterates the Lodger's guilt, ... or is it just Hitchcock's way of having his cake and eating it?' Definitely the latter, I think! Now, here's what I thought of The Rat. Novello plays Boucheron, an Apache - Paris gangster - who has a succession of mistresses until he meets Odile, a waif, played by Mae Marsh, and feels especially protective towards her. But one night in his regular hangout, a nightclub called The White Coffin, he encounters a lady from the upper classes, Zelie (Isobel Jeans), who is 'slumming' for the evening - she is the kept woman of a rich banker, Stetz (Robert Scholtz), who has allowed her to spend a night on the town with friends. (First they visit the Folies Bergère, then come on to The White Coffin.) Stetz is the film's villain. Although Boucheron flirts with Zelie, he intends no mischief; whereas when Stetz turns up at the nightclub and happens to see Odile, who is passing by, he immediately lusts for her. Right from the start, my impression was that Novello - who wrote the original treatment - was showing off his 'virility'. The first reel is little else but a demonstration of the character's insouciance and daring. We see him eluding two pursuing gendarmes by opening a grating, then hiding in the space underneath, and even cheekily taking out his pocketknife and cutting the shoelaces of one of the gendarmes who has stopped, baffled, on the grating! Eventually Boucheron arrives at Odile's tiny room in a poor-but-respectable quarter of the city; by now, he is smoking a cigarette which hangs jauntily from his mouth. Sauntering into the room, still smoking, he nods to Odile, hangs his cap on the wall (a deft throw of the pocketknife makes a makeshift peg), then seats himself at the table and, with a flourish, takes out a folded-up newspaper. (See frame-capture below. Btw, just visible at the top-of-shot is the alcove where Odile keeps a statue of the Virgin Mary to which she regularly prays.) Following Williams, I would say that this is all image-building by Novello, whose gayness was an open secret in the acting profession but carefully concealed from his huge public. His boyish good looks were his principal asset but they could have worked against him if they weren't countermanded, in effect, by the content of the films. One of Novello's biographers, James Harding, puts it like this: 'With The Rat Ivor established himself as the leading British film star of the time. The swagger he adopted in the main role compensated for the slightly effeminate look critics had up to then remarked on, and his air of cynical raffishness carried off the part with bravura.' But why, then, did Novello proceed almost immediately to make The Lodger - which, at a glance, might have seemed likely to offset most of the gains his 'image' had just achieved? (After all, there Mrs Bunting is heard to say that her lodger 'is a bit queer'.) Williams's answer to that question, which considers Novello's further work for Hitchcock on Downhill the following year, is elaborate - I'll leave it for next time. Meanwhile, here's my contribution. Novello knew that there was more to his 'image' than just undercutting any impression of effeminacy. An actor should have 'range' and 'depth', and his/her 'image-building' needs a positive side to it. In fact, as The Rat progresses, and melodrama begins to build - with Odile accused of killing Stetz - Novello is called on to show emotion, not just a set of gestures. There is even one scene towards the end when Boucheron is exhausted and momentarily seems at the end of his tether. The contrast with his initial raffishness is important dramatically. But so, too, is the fact that Odile's landlady (a strong old bird - she also tends bar at The White Coffin), played my Marie Ault, cradles Boucheron's head in her arms in a motherly gesture. It seems almost a proxy moment on behalf of Novello's legion of female fans - and in some ways anticipates Ault's role in The Lodger. To be continued.

September 13 - 2014

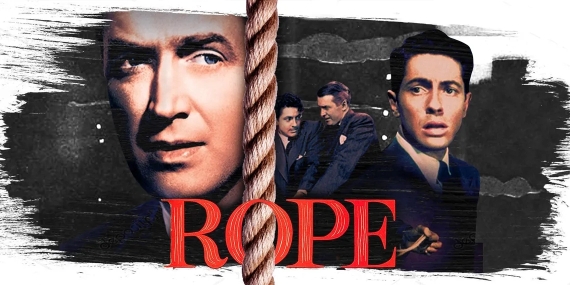

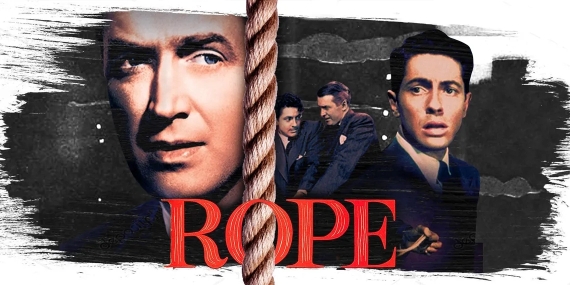

The Rope screenplay notes that from the moment Rupert returns to Brandon and Phillip's apartment, ostensibly to find his mislaid cigarette case, 'Brandon, from here on, is a madman'. (Brandon has just told Phillip, 'No one is going to get in my way now', and we see him load a revolver before opening the front door.) Actually, Rupert suspects the worse - but can hardly admit it to himself - for he secretly carries the rope that had served Brandon and Phillip as a murder weapon. He evidently plans to taunt the killers into a 'confession': shades of the cat-and-mouse game between Porphiry and Raskolnikov in Fyodor Dostoyevsky's 'Crime and Punishment' (1866). Indeed, when Rupert claims to find his cigarette case behind some books, both the audience and the killers know that he is lying, and that he has just put it there. From now on, Brandon's hand hovers near his pocket containing the revolver, and the suspense builds. It's alleviated by black comedy and double-entendre, of course, as when Rupert speaks of how 'pleasant' it is 'to sit here with a good drink and good company'. And soon, as if playing a guessing-game, Brandon challenges Rupert to imagine what may have happened to the missing David. Obligingly, Rupert - and the moving camera - re-create the moments leading to David's death (much as Maxim in the boat-house scene in the 1940 Rebecca describes the last moments of Rebecca before 'she stumbled and hit her head on some ship's tackle'). But suddenly Rupert notices Brandon's hand in his pocket, and must think quickly. Here occurs the last of the film's 'invisible' cuts (not counting the ones on black objects). From a shot of Brandon's pocket, representing Rupert's pov, the film cuts to Rupert's face, noticing. (See frame-capture below.) Turning away from the chest, he suggests that David's body could have been carried downstairs and put in the car. For the moment, Rupert is off the hook - but the arrogant Brandon won't have it. Driven by what the Freudian psychoanalyst Theodor Reik called 'The Compulsion to Confess' (the title of his 1925 book), Brandon immediately points out, 'You'd be seen ... You said yourself ... [whatever happened] must have happened in broad daylight.' And so we rapidly move to a showdown in which it's impossible to feel that we, the audience, at some level, are not implicated. I have already discussed this aspect, both above (e.g., entry for August 30) and elsewhere, notably in the essay "Melancholy Elephants" in Mark Osteen (ed.), 'Hitchcock & Adaptation' (2014). The gist of my point there is that Hitchcock knowingly took the climax of Rope, in which a flashing red, green, and white electric sign shines on the several characters in a room, from the novel 'Enter Sir John' (1929) by Clemence Dane and Helen Simpson (the novel on which Hitchcock's 1930 Murder! was based) - and that the novel's symbolism was used by Hitchcock to underline Rope's idea of complicity by all parties concerned, even the film's audience. 'Enter Sir John' is about the world of theatre, and the three colours are explicitly compared by the novel to the colours of the comic character Harlequin in the Italian Commedia dell'arte (which has been called 'pure theatre'). By extension, it's only fitting that the three main characters in Rope should be similarly bathed in Harlequin's colours, for they are all, ultimately, jesters in the game of life - fallible and subject to error. Or, as Shakespeare would say, they are all 'merely players' (cf. 'As You Like It': 'All the world's a stage,/ And all the men and women merely players'), something that the 'theatrical' look and feel of Rope, confined to a single 'set', constantly underlines. Essentially this is a compassionate view of life, not incompatible with Hitchcock's Catholicism. However, it is also of a universal significance, which was touched on this week in our Hitchcock discussion group. I posted: 'Hitchcock's position [in Rope is] that there is more to Life than the Id - just as [the philosopher] Schopenhauer [proceeded] from his basic insight about the nature of Will (or life/death force) to an "ethics of compassion" that saw how Will is everywhere responsible for suffering and that it can best be offset by compassion for its victims, i.e., all of us. ... [That is, ethics can] take account of the bigger picture, the plight of humanity as a whole - which Brandon can't see, thinking only of himself.'

September 6 - 2014

[Held over until next time. KM.]

August 30 - 2014

[Revised.] First, I'll finish my observation of last week, about how Rupert in Rope is a smoker (thus validating the moment when his gold cigarette case serves as his excuse to return to Brandon and Phillip's apartment after the cocktail party) ... It would be too 'obvious' if Rupert alone, of all the film's characters, were a smoker, so the screenplay includes a pointed scene where we notice that both Janet and Kenneth also smoke. (See frame-capture below.) No matter that this 'intimate' moment is a virtual Hollywood cliché, for that serves Hitchcock's characterisation nicely. Janet and Kenneth had once been close, and their manipulative host Brandon (the film's other smoker, I should note) seeks to bring them back together, thereby mocking their (as it were, clichéd) 'ordinariness'. He has just suggested to Kenneth that he 'switch on the radio or play some records ... a little atmospheric music goes a long way' - and now, besides watching the business with lighting-up, we listen to the audio cliché of a pop tune performed on the radio by the then-popular group The Three Suns. (By contrast, the only other diegetic music heard in the film is that played by Phillip at the piano: atonal music by Francis Poulenc who had just completed his first concert tour of the United States accompanied by baritone Pierre Bernac, his gay lover.) Hmm. During the week, on our Hitchcock discussion group, I noted that Rope's gay screenwriter Arthur Laurents had reportedly dated three male members of the film's cast! (See Charles Kaiser, 'The Gay Metropolis', 1999, p. 59.) In other words: John Dall, Farley Granger, and one other. Ruling out James Stewart and Cedric Hardwicke, that really only leaves either the actor playing Kenneth (Douglas Dick) or the one who plays the dead David (Dick Hogan). Reader, you guess! The point I was making was that the film's director, a good Catholic boy, and married to Alma, meanwhile observed all this from a distance, bemused by the passing parade and its rich 'characters'! And that this was reflected in the film. How different, I felt, from the director Pier Paolo Pasolini, whose Salo (1975) is devoid of characterisation, and coldly pornographic. This was in the context of another claim of mine (to our group's avowedly gay member, BD) that if there is one single text, besides Patrick Hamilton's original play ('Rope's End', 1929), that can be likened to Rope, it is André Gide's immensely lucid 'L'Immoraliste' (1902) - influenced by Friedrich Nietzsche and Oscar Wilde. There, the gay 'risk-taker' Ménalque is to the story's bisexual young narrator Michel as Rupert is to Brandon and Phillip, a sort of existential agent provocateur. (Note. Elsewhere I have argued that the character of Rupert derives from Wilde's 'Phrases and Philosophies for the Use of the Young', published in 1894, although, as Laurents's memoirs confirm, once James Stewart joined the Rope project the script couldn't develop that line any further.) Obligingly, BD recalled a remark of François Truffaut: 'Alfred Hitchcock makes films as Gide writes books - "to disturb"'! And it's so true! Here I pointed to Hitchcock's admirable (relative) objectivity, and how it had been presaged by Gide whose successive texts would critique the apparent position of others by him, earlier or later. Also, each text would put ideas in a human context. Here's a pertinent observation by Gide biographer Alan Sheridan: 'L'Immoraliste is not so much an apologia for Nietzschean ideas as an exploration of what can happen if such ideas fall into the hands of someone too weak to sustain them.' (Introduction to Penguin edition of 'The Immoralist', p. viii.) Not only does Rope suggest that none of us is without human weakness, but that none of us has the right to declare oneself above others, finally. At the climax, just before Rupert's denunciatory, 'Did you think you were God, Brandon?', the script gives him this: 'Now I know the truth .. that humanity cannot be divided into categories to suit our own ends. We are each of us a human being, Brandon, with the right to live and work and think as individuals. Yes, but with an obligation to the society we live in.' To come back to 'L'Immoraliste', it's worth noting that it is narrated by Michel in retrospect, now a sadder and wiser man, to a group of friends he has summoned to hear the cautionary story of his life so far. And after hearing it, their spokesman notes: 'By not condemning [Michel's] actions at any point during his long explanation, we were as good as accomplices. We were in some way implicated.' (p. 123) More next time, while concluding this brief look at Rope with an examination of its finalé in greater detail.

August 23 - 2014

Hitchcock's films from, say, Rebecca (1940) onwards, typically come complete with back-stories, and Rope is no exception. While we're not told the details of how Brandon and Phillip first met (perhaps in prep school where bachelor Rupert was house-master?), yet we do know that they have been firm friends for many years. And that Brandon clearly has 'influence' over his partner, probably to the extent of being the instigator of the murder of young David Kentley, i.e., a homosexual 'thrill killing' designed to bond the partners and to show their intellectual superiority which they rationalise as being in keeping with Nietzsche's ideas propounded by Rupert, their mentor (and ersatz father-figure). We also know such things as that Brandon's wealthy mother owns a farm in Connecticut where Phillip has long been welcome, and which even Rupert has visited. Also, we know that Brandon had an unlikely affair with Janet before she turned to, first, Kenneth and then David. (So is the killing of David partly Brandon's 'revenge' for being dropped by Janet? Likewise, is Rupert's interest in Nietzsche a way of compensating for his 'impotence', symbolised by his limp from a war-wound but which can be further interpreted as a symbol of his own gayness? Note his bizarre remark about the aging housekeeper Mrs Wilson: 'I may marry her.') Equally, given that the film's three principal males are a dandified show-off (Brandon), a sensitive artist/musician (Phillip), and a conscientious 'super-ego' figure (Rupert) - who yet has affinities with the other two - we may be allowed to see Hitchcock's long interest in making the film as due to his feeling an affinity with the overall situation (including an 'obsession' with murder) - and which, via Rupert, he seeks to 'exorcise'. (For further reason why Patrick Hamilton's play would have appealed to Hitchcock, see August 9, above.) Now, I said last time that Rope is vastly different from Pasolini's Salo - a film that came up on our discussion group recently - precisely because Hitchcock's film 'about' homosexuals is full of characterisation whereas Pasolini's homosexual view 'of' sexuality per se is almost devoid of characterisation, a reading clearly supported by Gary Indiana's monograph on Salo (BFI, 2000): 'Although Salo is the ultimate chamber piece, not all of its figures emerge as "characters". On the contrary, none of them do.' (p. 34) I find it impossible when watching Salo (which I told our group I consider 'hard-to-take and eventually tedious') not to think that its parade of pornographic tropes isn't the result of its director's reported near-nightly 'cruising' of the gay scene. And that its content is vastly different from the relatively 'rounded' characters and psychologically astute observation that inform Rope. Hmm. When Hitchcock spoke to Oriana Fallaci (cf. August 9, above) about his understanding of the sexual proclivities of Nordic women - and English women, too - she understandably asked him, 'Forgive my asking: but how do you know these things, Mr Hitchcock?' To which he replied, frankly enough, 'What a question! I listen to what people say, I find out about things. Obviously the information is second hand. Scientists ... know that if you mix one powder with another powder you'll be blown up. But they don't have to be blown up in order to know it.' (p. 91) So there you have two different aesthetics! And yet both films refer to Nietzsche, and seek to say things about society in general. (Pasolini's Marxism is another aspect of that poet-filmmaker.) Interestingly, Indiana claims that 'Salo engages voyeurism rather than empathy' (p. 57), yet although Hitchcock is often spoken of as disposed to voyeurism, you would have to say that there is an admirable balance of those two elements in Rope - whereas Salo feels decidedly unbalanced. More about these matters another time. To conclude, here's something about Rope that I had not really noticed before, and which goes to show the care that went into the script. Rupert is a smoker. He is smoking a cigarette on his first entrance and quickly goes over to the piano where Phillip is playing in order to stub out the cigarette, while remarking, 'Your touch has improved, Phillip.' (See frame-capture below.) Yet within minutes he lights up again. We see him take out his gold-plated cigarette case from an inside pocket of his impeccable grey suit. He is, you must feel, an urbane individual, possibly with something preying on his mind, who yet carries himself well. And of course that gold-plated cigarette case has a vital role to play at the film's climax ... More next time.

August 16 - 2014

Actually, the first cut (of at least four) in Rope comes right at the start, after the camera, which has been looking down into a New York street ('in the East Fifties', according to the script), pans to the window of Brandon's upper-story apartment where the shades are drawn - and we hear a literally strangled male cry. Next minute, we are inside the darkened apartment, forced to watch the moment of death of a young man killed by two strands of rope drawn around his neck by the gloved hands of Phillip (Farley Granger). Meanwhile, Phillip's partner, Brandon (John Dall) - whom the script calls 'the accessory' - has been restraining the victim and using gloved hands to do so. The fact that both partners wear leather gloves is one instant sign that the murder is pre-meditated. Next, the partners lift the body into an adjacent chest, and close the lid ... Now to come back to that cut. It isn't to a reaction-shot of a character exactly, because as yet we haven't met any characters (just observed a policeman down below ushering two schoolchildren across a pedestrian-crossing). Nonetheless, you could say that the cut is 'demanded' by the audience's aroused curiosity, our urge to know. After the strangled cry, Hitchcock holds on the window for a second or two to allow that urge to build. Then he cuts. But we scarcely notice the fact of the cut because our attention is diverted by, first, our impatience to know what has happened and, second, our instant shock on seeing the dead boy. In effect, the cut is invisible. The film will apply this 'invisibility' technique at least three more times - and in each case link it to an actual reaction-shot. My point, from last time, is that Hitchcock uses audience psychology - specifically, our not noticing what is essentially 'invisible' - to make us feel that we have experienced in Rope one continuous 'shot', and have been 'locked in' with the characters whose story is somehow ours. The film doesn't actually state that we are implicated in what has happened, yet implies it. Thus the film is a 'cautionary tale', albeit more elaborate than the one of Brandon's about a maiden on her wedding-day who got trapped in a chest with a spring-lock, and whose skeleton was only found years afterwards. Shortly, I'll expand this topic by comparing a notorious film of Pier Paolo Pasolini, Salo (1975), which I had occasion to watch this week. However, let's concentrate for now on Rope's 'invisible' reaction-shots. The first comes with the arrival at Brandon and Phillip's cocktail party of Janet (Joan Chandler), the missing boy's current girlfriend: as Janet enters from the hallway, she is observed from the next room by Kenneth (Douglas Dick), her previous boyfriend - and a virtually invisible cut as she says 'Hello Kenneth' shows us his surprise and mild embarrassment at seeing her. (The manipulative Brandon has effectively set the two people up, manoeuvering to bring them back together, or 'playing God' as the script will pointedly have it.) The next such moment occurs at a dramatic climax when the nervous Phillip has reacted angrily to Brandon's story about his strangling chickens: 'That's a lie!' The line virtually demands a reaction-shot and that's exactly what Hitchcock gives us - by cutting to the instantly-thoughtful face of Rupert (James Stewart) and holding on that view for some twenty seconds (see frame-capture below) while the other guests' conversation resumes off-screen. (Again our psychology helps make the cut 'invisible' - and now, note, we begin to feel that it's only a matter of time before Rupert solves the mystery of what is going on.) And the third reaction-shot utilises our growing sense of suspense. The suspicious Rupert has just remarked to his two hosts, 'There's something upsetting you a great deal', when the voice of housekeeper Mrs Wilson (Edith Evanson) is heard from off-screen: 'Excuse me, sir' - and we suspect that disclosure may be only seconds away! So Hitchcock takes the opportunity for another near-invisible cut (to disguise the next reel-change) by showing us the deferential Mrs Wilson as she completes her speech: 'There's a lady phoning for either Mr Kentley or Mrs Atwater.' She is actually addressing Brandon but momentarily we think that she might be about to take her cue from Rupert's remark and reveal to him the evidence he is searching for! The script is often hugely clever in just such nudging-along ways! But now notice something else: how each of those reaction-shots isn't just linked to a particular character, it actually helps disclose a character, that is, something about the person speaking or the person/s addressed. This fully supports the claim made by the film's screenwriter, gay playwright Arthur Laurents (on the Rope DVD), that Rope is one of the best films ever made about homosexuality - precisely because it is concentrated on character/s. By contrast, next week I'll go into some detail about why Pasolini's Salo, while it arguably has a homosexual outlook, is bereft of character (and infinitely more pornographic). As Gary Indiana's study of Salo (BFI, 2000) says, 'the subjective life of anybody in Salo is terra incognita' (p. 42).

August 9 - 2014